Top stories this week:

— Dexter Filkins’ informative piece on Turkey, its prime minister, and the concept of “the deep state (great first line I’d like to hear read aloud: “Not long ago, at a resort in the Turkish town of Kizilcahaman, Prime Minster Recep Tayyip Erdogan stood before a gathering of leaders of the Justice and Development Party to celebrate both his country and himself”);

— Daniel Zalewiski’s meticulous article about Christian Marclay’s meticulous creation of his work, especially his 24-hour film mash-up, “The Clock”;

— Peter Schjeldahl’s entertaining and infectious rave review of the Whitney Biennial;

and last and possibly best: Dahlia Lithwick’s review of Dale Carpenter’s book “Flagrant Conduct,” in which she encapsulates Carpenter’s revelations about the true story of Lawrence v. Texas, the landmark Supreme Court decision ruling sodomy laws unconstitutional, a major victory for the gay rights movement. History has handed down the case as one in which Texas police broke into a private home and discovered two guys in bed having sex and busted them for it. Lithwick writes:

“Two of the four officers who entered the apartment reported seeing two men having sex. Yet one officer reported seeing anal sex and the other remembered seeing oral sex. The other two saw no sex at all. At least three saw [a] homoerotic drawing [of James Dean with oversized genitals].

“Carpenter’s painstaking interviews establish that Garner and Lawrence not only weren’t having sex but were clothed (Lawrence was in his underwear, preparing for bed) and in separate rooms. This makes sense if you consider the timeline that night (Eubanks [Garner’s drunken boyfriend, who’s the one who called the cops, saying somebody was being threatened with a gun] was ostensibly just slipping out to buy a soda) and the fact that there was yet another man still in the apartment. But the defendants’ accounts were never disclosed to the media. Nor was the existence of Lawrence’s longtime boyfriend, Jose Garcia. Requests by lawyers that the privacy of the two plaintiffs be respected meant that little attention was ever paid to their personal lives. Lawrence and Garner, for their part, were given strict instructions by the lawyers to shun the press. (Carpenter is careful throughout to show that none of the civil-rights lawyers lied or misrepresented the facts.) The litigation strategy, as the case made its way up through the trial courts and appeals courts, was deliberately framed to highlight the need to decriminalize homosexual conduct as a means of recognizing and legitimatizing same-sex ‘relationships’ and ‘families.’ In short, the legal issue was not that free societies must let drunken gay Texans have sex; it was that gay families around the country, in the words of one of the lawyers in the case, ‘are essentially just like everybody else.’ ” Fascinating. Read the whole piece here.

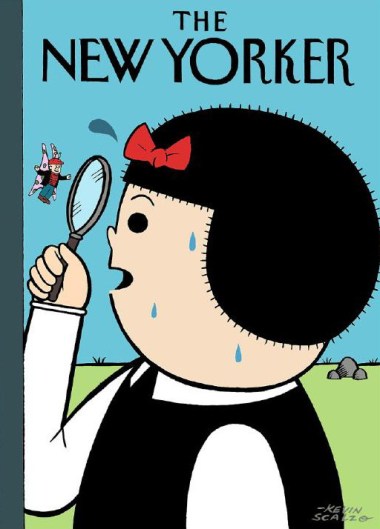

And then there’s Bob Staake’s cover, which must have made New York Times columnist Gail Collins very happy. Have you noticed that every single one of her columns, without fail, mentions that Romney took his family on vacation once with the dog strapped to the top of the car? It’s a running joke that never fails to crack me up.