Culture Vulture had a rich international weekend of activity.

Friday night I returned to the Irish Arts Center, where I saw a wonderful evening of Irish poetry just two weeks ago. The occasion for this visit was to see Céilí, a fascinating collaboration between Darrah Carr Dance, a company of fresh-faced youngsters devoted to invigorating Irish dance traditions, and Seán Curran Company, a funkier crew whose leader came up through the Bill T. Zones/Arnie Zane Company’s brand of innovative modern dance. The title of the show refers to a house party, and the evening did have a light-hearted, celebratory feel as various combinations of dancers took turns doing their party pieces. They mostly danced to sublime live accompaniment by fiddle-guitar duo Dana Lyn and Kyle Sanna, except for one virtuosic handclap-and-foot-stomp duet (“Box Tops”) by Trent Kowalik and Lauren Kravitz – all the more impressive because at this performance Kowalik went on as understudy for Benjamin Freedman; Evan Copeland covered Freedman’s other duties that night. Throughout the evening I couldn’t take my eyes off Kowalik and Copeland. Kowalik, one of the three kids who won the Tony Award sharing the title role in Billy Elliot: The Musical on Broadway, is tall and light-footed and seemingly effortlessly maintains the signature verticality of Irish dancing. Handsome bearded Copeland, a longtime Curran associate, stood out for the precision of the lyrical shapes his dancing created. It was a dense, continuous hour-long expression of joy.

A community jam session was taking place in the lobby as we left to go around the corner to Ardesia Wine Bar for a delicious dinner of small plates – portobello fries, tacos, charcuterie – and a bottle of Spanish mencia.

Saturday afternoon – More joy burst from the stage of the Atlantic Theater Company’s Linda Gross Theater from the first notes of Buena Vista Social Club, the thrilling new musical built around the legendary Cuban musicians who appeared on the 1996 album (put together by record executive Nick Gold, guitarist Ry Cooder, and musical director Juan de Marcos González) and in Wim Wenders’ 1998 documentary. For the stage production, developed and directed by Saheem Ali, playwright Marco Ramirez crafted a narrative to weave together the histories of five key musicians and their lives in Havana in 1956 (pre-Castro) and 1996. He may have borrowed a page from Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom to portray Omara Portuondo as a demanding diva around whose whims the recording sessions take place. But Ali has assembled an incredibly talented cast – Natalie Venetta Belcon as Omara, Kenya Browne as her younger self, Renesito Avich as Eliades Ochoa, Julio Monge as Compay Segundo, Mel Seme as Ibrahim Ferrer, Jainardo Batista Sterling as Rubén Gonzalez, and Jared Machado, Olly Sholotan, and Leonardo Reyna as the younger Compay, Ibrahim, and Rubén – and he and music director Marco Pagula put together a spectacular band.

As if the music blasting from the stage wasn’t deliriously exciting enough, Patricia Delgado and Justin Peck fill the stage with energetic sexy choreography for six terrific dancers. Anulfo Maldonado’s nimble sets, Dede Ayite’s dazzling period costumes, and Tyler Micoleau’s bold lighting all contribute to the visual excitement. For anyone familiar with the album and the film, layers of feeling can’t help piling on top of each other watching these extraordinary singers and musicians exude love and devotion for Cuban music. I can’t imagine this show won’t move to Broadway, where I hope to revisit it, but I don’t think I’ll ever forget the joy of sitting in the third row of an intimate Off-Broadway theater receiving the blessing of this gorgeous show.

Our friend Sari and her adolescent son Sam met us afterwards for a stroll through the Whitney Museum, whose current offerings introduce museumgoers to Japanese-American artist Ruth Asawa (I first learned about her from the postage stamp in her honor; see “Untitled” above), African-American painter Henry Taylor, and in the project room Indigenous sculptor Natalie Ball. I never know what’s going to catch my eye at the Whitney.

I felt indifferent to most of Taylor’s unbeautiful paintings, though I thought his room of portraits of artists was witty (Tyler the Creator on a suitcase, above; Deena Lawson “in the Lionel Hamptons,” below) and his installation dedicated to the uniforms of the Black Panthers arresting.

A complicated exhibition called “Inheritance,” curated by Rujeko Hockley, riffs on lineage and artistic legacies. Andrea Carlson’s ambitious Red Exit weaves evocative native symbols with abstract images.

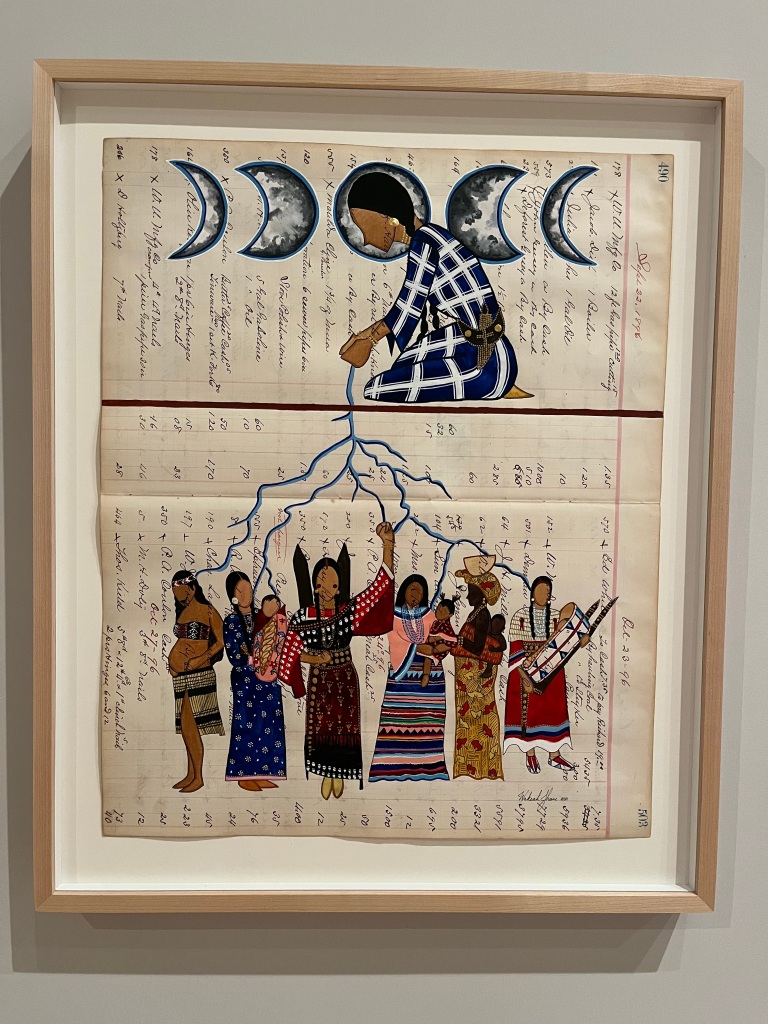

Wakeah Jhane’s Grandmother’s Prayers goes there with one resonant image.

And I found multiple ways to appreciate Sturtevant’s homage to Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s 1991 installation “Untitled (Blue Placebo),” in which viewers are invited to take a piece of blue-wrapped candy from a large rectangular field of them.

That tasty caramel tided me over until we had dinner at Osteria Nonnino on Horatio Street – paccheri with the spicy house sausage-and-vodka sauce and a bottle of nero d’avola.

Home from our expedition, Andy and I finished watching season 1 of Reservation Dogs on Hulu, one of the weirdest TV series in an era of extremely weird TV series. RezDogs mashes up Schitt’s Creek with Somebody Somewhere but in a blandly suburban Native community in Oklahoma. Taika Waititi co-created the series with Sterlin Harjo, and it has all the eccentricity and casual/jokey supernatural eruptions familiar from Waititi’s other work (Thor: Ragnarok, Jojo Rabbit, What We Do In The Shadows). The all-native cast is full of wonderful actors I’ve never seen before, some of them very young (see above), all of them masters at deadpan comedy. I usually give myself permission to enjoy the luxury of subtitles because dialogue flies by so quickly, but with this show it’s especially fascinating to read the native words that show up as regularly as the affectionate sobriquet “shitass”; also fascinating to see that the screenplay spells “Indian” as “NDN.”

A weird thing happened just as we were turning in for the night. A couple of drunken guys got into an altercation on the street in front of my building, and the one getting beat up pressed all the buzzers until someone buzzed them in, at which point they proceeded to tromp up and down the stairs yelling and fighting. “Ehh, macho straight guys, let them settle it amongst themselves,” I thought. But then I heard a woman scream, so I called 911. The scuffling and yelling went on, someone spat on someone, which escalated the fighting. Eventually the friends of the fighters dragged them away. Shortly thereafter four wet-behind-the-ears NYPD officers showed up, looking scared and clueless. The fighters had apparently grabbed two fire extinguishers and sprayed each other with them, so a cloud hung over the hallway. Saturday night in the big city.

Sunday afternoon we trekked down to the East Village to see The Boy and the Heron, Hayao Miyazaki’s valedictory film, a beautiful and trippy fantastic-voyage mythological yarn full of tiny references to characters and images from the Studio Ghibli pantheon. We came home and I made two fairly ambitious dishes from the New York Times Cooking app – a kale and squash salad with almond-butter vinaigrette (per Ali Slagle) and spicy roasted mushrooms with polenta (thank you, Yotam Ottolenghi!).

Reading the Sunday New York Times fed my soul with a couple of items. The Sports section on Sunday featured a full-page article about football star Jordan Poyer headlined “A Safety Finds Enlightenment In Ayahuasca.” Dan Pompei compiled a respectful and factually accurate summation of plant medicine as Poyer talked openly and vulnerably about how the medicine helped him bring his alcohol abuse under control. Also, in the Times Magazine “Talk” column, David Marchese interviews David Byrne, who speaks thoughtfully and personally about change. While discussing the Buddhist concept of no-fixed-self and how what we think about ourselves can change, Byrne is asked how he himself has changed.

“Wow. Well, I realized quite a few years ago that as much as I might like to deny it, I harbored a lot of racial biases. At that point, a younger liberal person would say, Oh, I’m not racist, or I believe in equality. But at the same time, I was aware that I was also harboring these inner biases that I could occasionally sense. I realized I may rationally say that I’m not racist, but I have implicit biases that I would like to deny but they’re there. Overcoming those is more difficult than just rationally saying, Oh, no, that’s not right. Those beliefs and biases, whether they’re about race or women’s rights or whatever they might be, those things can take a long time to fundamentally change within us. I would like to think that I’ve been engaged in that process and was trying in [his Broadway show] American Utopia.”

Marchese asks, How do you do it? “Good question. Let me think of some examples. People might say, Germans don’t have a sense of humor, or all Italians are really passionate; you might see a bunch of kids on a street corner and think, There’s trouble, I’m going to avoid them. In my experience, the way to work through some of that stuff is just to get to know other people as individuals a little bit better, and that starts to break those biases down. But that’s a slow process. And for somebody who’s not maybe the most social person in the world, that takes some work.”

I so appreciate David Byrne’s honest introspection. He sat in front of us when we saw David Adjmi’s superb play Stereophonic at Playwrights Horizons (he later wrote an essay about the play for the PH website), and I watched him chat freely with the fans around him, which I’ve hardly ever seen celebrities do in public. So I feel like I got to witness him stepping out of his comfort zone and practicing “getting to know other people as individuals.”

I’ve been thinking about how so much of the divisiveness in the world these days seems to boil down to people’s tolerance level for behaviors, identities, and beliefs that are different from their own. How much of that is learned, how much is inherent, how much is malleable? I feel like I have not only a huge tolerance but a deep and abiding appetite for experiencing difference. Was I born that way? Some of it surely has to do with realizing I was gay at an early age and looking at the world through a queer lens. I like the way another Times Magazine contributor, Venita Blackburn, put it, writing about the animated Japanese series Sailor Moon: “queerness is not just sexual…queerness is also existing under duress, where one’s instinct toward self-determination is a kind of spiritual expanse that grows from deep within the body and psyche then cascades out into an eventual shape unlike most others.”

But the other circumstantial piece that overwhelmingly influenced my experience of difference was growing up as a military dependent. My father grew up as a poor, uneducated farm kid in culturally homogeneous small towns in the Midwest. He didn’t lay eyes on a black person until he was 12, by which point he’d been indoctrinated with all the racist stereotypes of midcentury American culture. Ironically, his joining the U. S. Air Force and raising four kids meant that we got to travel all over the country and to Japan, which automatically exposed us to people, food, landscapes, and attitudes unlike our own.

Lucky me to have had that upbringing, and lucky me to have landed in New York City, where my craving for exposure to difference and other cultures can never be exhausted.