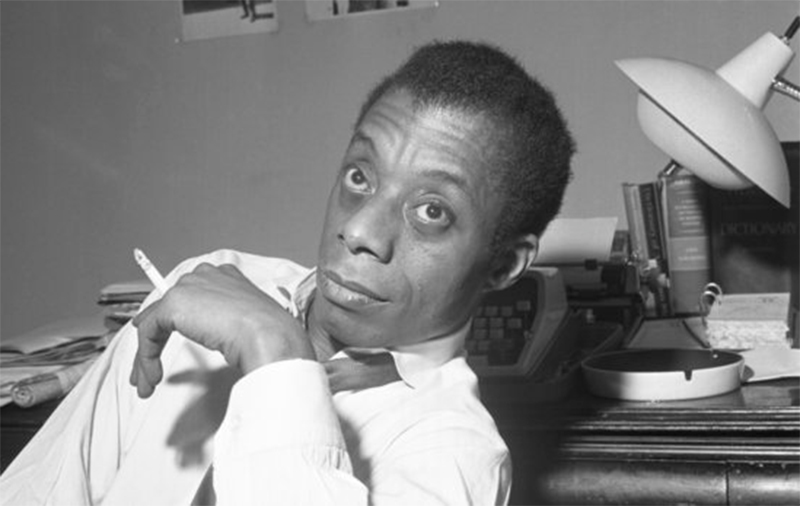

The Wooster Group’s contribution to pandemic theater-adjacent entertainment debuted a couple of weeks ago: “Fran and Kate’s Drama Club,” a monthly Zoom chat between Frances McDormand at home and Kate Valk from the Performing Garage, where the company is rehearsing a new production of Brecht’s The Mother. The Drama Club’s first episode showed some short documentary films by Julie Lashinsky from the Wooster Group’s extensive archives and brought on Hilton Als as talk-show guest. Als will return for the second episode, which happens Thursday February 25. See here for details and tickets.

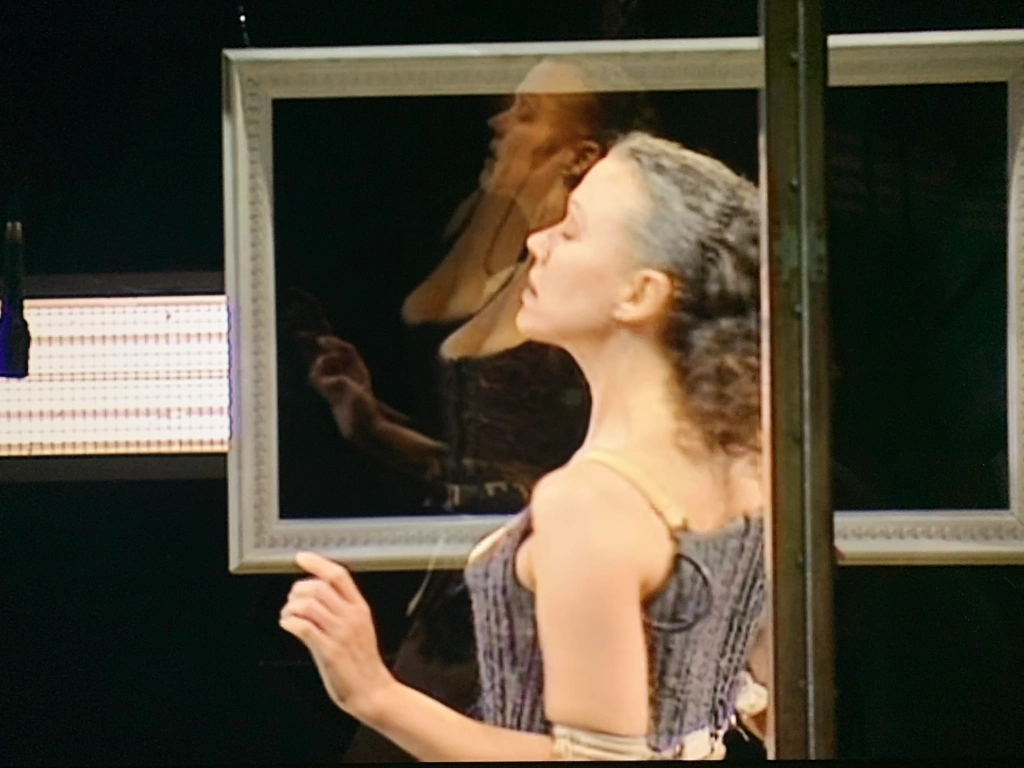

Fran and Kate met in the process of creating To You, the Birdie! in 2000. This was the Wooster Group’s adaptation of Racine’s Phèdre, based on the translation by the late Paul Schmidt, a renowned man of letters who was a member of the Wooster Group for several years. Directed by Elizabeth LeCompte, the production featured the core Wooster Group actors – Kate Valk as Phèdre, Ari Fliakos as her stepson Hippolytus, Scott Shepherd as Theramenes, and Willem Dafoe as Theseus – joined for the first time by McDormand, a Yale-trained stage actor who’s spent most of her career acting in films, including Fargo, for which she received an Academy Award, playing Phèdre’s maidservant Oenone.

I’ve owned the DVD of the Wooster Group’s To You, the Birdie! since they first made it available in 2011, but I never watched it until last night. Andy had never seen the show but had heard me talk about it numerous times, so we watched the whole thing. The single camera video couldn’t possibly convey the vibrancy and presence of the live show, so it was somewhat disappointing to me. I was more excited by the documentary clips that came as a DVD extra. But I was astonished at how much of the story and the play came through for Andy, much more detail than I’ve ever comprehended. We talked about how the first time you see a Wooster Group production you’re watching for narrative, for storyline, and that is often extremely frustrating because LeCompte (I’m going to call her Liz) could care less about that. When you see the show again, you relax your story-seeking mind and let the multisensory experience wash over you, letting your eyes wander all over the stage, where there is always something going on, sometimes comprehensible, sometimes cryptic. Impossible to see it all.

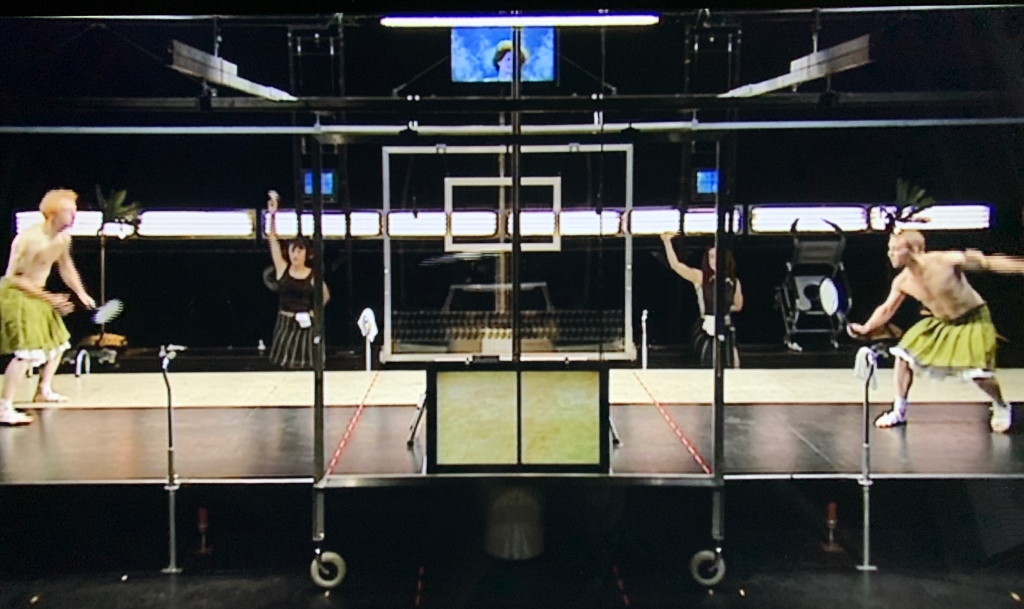

After seeing the show at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn at least twice (possibly more – and I might have seen some work-in-progress showings), the impressions I retained were stark and scattered: Ari Fliakos’s flawless naked body, Scott Shepherd’s phenomenal vocal performance speaking all of Phèdre’s lines sitting in front of two microphones at the back of the stage, the noisy and hilarious badminton games, the heightened sound score throughout (including snippets of female harmony singing created in collaboration with Suzzy Roche), Kate Valk’s absolutely diva-esque commitment to embodying Phèdre (with all the crazy things this staging asks her to do), Frances McDormand’s equally fierce commitment to ensemble playing.

One of the pleasures of following a company over time is watching beloved performers stretch and grow and do different things and build on previous performances. Opera buffs and balletomanes can get very geeky about bodies of work. I loved following the Twyla Tharp company in the early days, whose names and personalities I knew as well as the members of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. The core Woosters (Kate, Ari, and Scott) are absolutely rock stars to me, and I enjoy not only their bravura performing skills but also the humor embedded in the nutty, sometimes perverse things they (under LeCompte’s direction) push themselves to do. Case in point: throughout To You, the Birdie! all three of them repeatedly scratch or wipe their crotches, pits, or butts and then sniff their fingers or the towel afterwards. Like all running jokes, it gets funnier every time you notice it.

And then there’s the crazy scene where Phèdre is receiving some kind of colonic treatment conducted by a trio of female attendants holding a douchebag and insanely long drainage pipes while Hippolytus is holding the queen steady on an awkward porta-potty contraption. And the whole time Kate and Ari are playing some kind of game where she’s nibbling or licking his naked torso and trying to feel him up discreetly and he’s swatting her hand away. Some of this is just impy fun, but it’s never unrelated to the essence of the story being told, which in Birdie/Phèdre revolves around the humiliations of unrequited love, physical intimacy, life in a body.

After watching the video, I got inspired to haul out Andrew Quick’s fantastic 2007 scholarly volume, The Wooster Group Work Book, for which he pored through all the rehearsal tapes and written notes for five Wooster Group productions. I thought I’d devoured the whole book when it came out, but I discovered that I’d read all but the last section about To You, the Birdie! So I had the delightful experience of reading all the documentation and Quick’s interviews with Liz and Kate having just watched the show again. I’d heard that the project originated from Kate’s desire to play a queen, having played any number of maids and functionaries in Wooster Group productions. She brought in Schmidt’s version of Phèdre and the actors read it aloud, but Liz found the text boring and struggled to find a way to make it come alive, which only happened when they borrowed from Japanese theater the idea of one performer (Kate) playing the physical character while another (Scott) gave the vocal performance. Hearing a male voice speaking Phèdre’s lines reminded Liz of Paul Schmidt, so in some way the production developed as a tribute to him. (Schmidt died in 1999 of AIDS at the age of 65.)

Badminton was always key to the staging. “I usually need some kind of distraction, so I can think in the space,” LeCompte told Quick. “I’ll get people doing something that I can watch in the space and this lets me consider the possibilities without them all sitting around waiting for me, because I’m much slower than they are. So, I’ll often start with a game or something like that. So no, I had no idea how the badminton was going to work out. I was just pretending that I knew what I was going to do with it…I was battling to get some irony into a sincere performance and an idiotic text.”

The Wooster Group has always made sophisticated, eccentric use of video and sound technology in its theater pieces. Two practices that began as experiments have become central to the company’s performing style: in-ear devices (like the kind through which TV producers communicate to on-air newsreaders) and TV monitors playing clips that only the performers can see. Once I became aware of these tools, I’ve been wildly curious to know what information pours into their eyes and ears that the audience isn’t privy to. Sometimes the actors are receiving their lines, freeing them from the pressure to memorize; other times they’re hearing something completely unrelated to the work they’re performing. For this show, it turns out the director was sitting in the audience whispering directions and encouragement throughout the performance.

AQ: The fact that it’s you giving the instructions to the performers via the in-ear device seems to make perfect sense in To You, the Birdie!

Liz: I don’t do it in any other piece. I have no desire to.

For this piece, the TV monitors played scenes from Marx Brothers movies and dance performances by Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham. Unbenownst to the audience, the performers interact with these video clips according to an elaborate, tricky set of rules devised during the development of the piece. The TV monitors present the actors with gestures, facial expressions, movements, or video effects to imitate with their bodies, sometimes tightly choreographed, sometimes left to improvisation. It sounds impossibly difficult to juggle these various tasks; it sounds a little monstrous, as if the director is manipulating the actors by remote control. But that’s what makes the Wooster Group so exceptional. They approach these complicated performance scores with the verve and skill of Olympic athletes while also looking like kids having fun playing.

In this passage from The Wooster Group Work Book, Quick’s questioning teases out of LeCompte a fascinating exploration of the difference between egotism and narcissism.

Liz: I like to set things up and steer them out of control.

AQ: I remember you talking about this in relation to the actors responding to the material that’s on the TV monitors that the audience doesn’t get to see. You describe it as something between imitation and sketching. You seem to want the performer to be working off the material in a way that allows them to bring a certain abstraction to their response. The relationship is natural, but a little off-kilter, but always done in real time.

Liz: Yes, doing something in real time.

AQ: It’s hard for actors, isn’t it?

Liz: Well, it depends on the actors. It’s not hard for Scott or Ari; it’s not hard for Katie. They do it naturally because it’s really the basis of great acting. I think the problem for a lot of stage acting is that it’s so often concerned with the actor’s desire to make sure that he or she is connecting with the audience. So, there’s always this little thing, this patronizing thing, that they are always one little second ahead of the audience, telling them what they should feel and what is coming next. I don’t want performers to be responsible for this. This should be the responsibility of the piece as a whole. It’s not down to individual performers.

AQ: So the ego of the performer has to push to the back?

Liz: In some ways, in other ways it’s pure narcissism. You have to have a certain kind of narcissism because you have to trust that the audience will watch whatever you do. A lot of actors have egoism, but they don’t have this kind of narcissism. Maybe, the egoism comes from film, where the actors always want to make sure that they are doing something important – this is so different to the narcissist, who simply doesn’t care.

AQ: This is quite a demand that you’re making of actors – to relinquish that control.

Liz: A lot of people I work with can’t do it, especially performers new to the company. For instance, Frances wouldn’t wear the in-ear device, she refused point blank – not that I demanded it of her. It was offered to everyone and everybody wanted to use it, except Frances. But for me, the fact that she didn’t take up the offer was brilliant.

AQ: Because of the role she was playing?

Liz: Partly, yes. But also because, without the in-ear, she’s the only one who doesn’t know what’s going on. She’s not in control because I can tell people on stage that she’s in the wrong place and I can have them move her, change her position – so she has to respond to the impulse.

AQ: It’s fascinating that in one of the rehearsals Frances is trying to persuade Kate to take the in-ear out.

Liz: Fran was going around to everyone and saying, “Take the earpiece out – rebel, rebel,” which I loved. That was exactly what I was looking for in Frances’ performance.

AQ: Because Oenone is so rebellious in the play?

Liz: Yes. So, I needed to channel this rebellious energy in her actual performance. Frances would be great in rehearsals, because she was really rebelling against me. But then, when we would go into a performance, she would suddenly become an actress and all that fun and naughtiness, which was directed at me, would disappear. I would say, “What happened to that energy you had in rehearsal?” I knew she was acting, that she was kidding me. I wanted to retain that quality she had in rehearsal in the performance.

I’ve often understood the various technological devices that operate in Wooster Group theater pieces sometimes as expressive sculptural objects – non-human characters in the show – and sometimes as masks of a sort. In the closing essay of his book, “Only Pragmatics?,” Quick writes very perceptively about how the Wooster Group performers use masks for liberating and expressive purposes.

When Valk speaks about what might be at the “root” of her own mode of performance in these works, she often invokes the metaphor and the physical reality of the mask to describe a means for moving beyond her own desire to generalize and control. According to Valk, the mask can appear in many guises. It is most obvious in the use of blackface in Route 1 & 9 (1981), L.S.D. (…Just the High Points…), and The Emperor Jones (1983), but it is also at work in the persona of the facilitator in Brace Up! And Fish Story, and in the on-stage relationship with the video camera, the TV monitors and in-ear technologies in House/Lights and To You, the Birdie! (Phèdre). The mask, however, is not solely a device that disguises and hides the personality of the performer. Nor can it be explained as a Brechtian device to expose how the operations of power and ideology shape social structures through the non-psychological medium of gestus. The mask has three functions. It establishes a sense of distance between the performer and the audience, creating a barrier between a two-way process of potential psychological identification; the performer with the audience and the audience with the performer. The mask also pushes aside the burden of always having psychologically to embody the character that is formed in the fictional world being negotiated on the stage. Finally, and perhaps most important of all, the mask works to displace the performer’s construction of their own subjectivity, the requirement psychologically to be themselves on stage. In this sense, the mask operates as a mean through which the performer is able to let certain notions of the self fall away. This leaves the performer free to engage as immediately as is possible with what the stage presents to them. In an unpublished interview from 1991, Valk explains this process by referring to the function of the mask in Noh Theater: “They say the mask is the device that allows for ‘spiritual possession’ because you deny your own self by donning the mask, and then you deny the existence of the mask.” In the Noh tradition, the mask acts as a barrier to the representation of a performer’s subjectivity. Then, in a crucial second stage, where the mask itself is denied, the performer moves into the complete state of dispossession (thus able to be spiritually possessed), which allows contact with the immediacy (the reality) of the on-stage experience. This is why the use of the mask is such a liberating device for Valk: “You truly discover through this two-step process of denial – that by denying your own physicality, and then by going a step further within your own consciousness to deny the existence of the mask.”

A footnote at the very end of Quick’s book led me to an essay I’d been looking for since I encountered it in the program notes for The Emperor Jones and Fish Story on tour in Europe. In my memory it was a long essay by LeCompte about watching TV as a form of meditation. I had it wrong. It was two pieces, a very short Roland Barthes-like list of “Rules for TV as Meditation” and then some “Notes on Form” compiled during the development of Brace Up! bouncing off of an essay about cinematography by French filmmaker Robert Bresson.

- The TV monitor is visible to the TV performers and is used as a mirror of themselves. The mirror/monitor is used as a means of transformation from self to “more self.”

- Actors are searching for masks of themselves — not for character. Who they are on the stage is who they are on the stage — period. They must be more “themselves” than in life.

- Approach the play as a monologue of the playwright’s, not a dialogue among the “characters.”

It’s not necessary to know any of this to see and enjoy a Wooster Group performance. And even knowing these things doesn’t necessarily explain what you’re watching. It just makes this dense, vibrant, multilayered work that much more alive with mystery.