An especially good issue of the magazine, starting with the cover (“Promised Land” by Christoph Niemann), a reminder that the first European settlers on this continent arrived uninvited, and not too many of them bothered to learn the language(s) the Natives spoke.

By design or happenstance, this issue is anchored by three strong reporting pieces about renegades and innovators having a big impact.

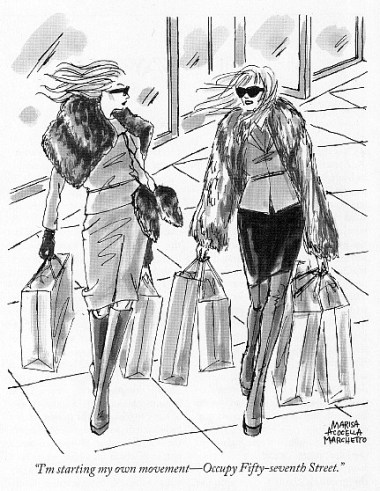

Mattathias Schwartz’s piece on Occupy Wall Street goes beyond anything I’ve read in pinpointing the key individuals responsible for launching and maintaining a nascent grass-roots movement that profoundly eschews the notion of leaders. Not only does it shed light on Kalle Lasn and Micah White, the unlikely duo at the heart of the Canadian-based anti-consumerism publication Adbusters, but the article name-checks a couple of people crucial to putting OWS in gear: 26-year-old Justine Tunney (one of several transgender anarchist activists who collectively responded to Lasn’s now legendary call for the occupation) and Marisa Holmes, a 25-year-old anarchist and filmmaker to whom people listen when she speaks.

George Packer contributes a fascinating profile of Peter Thiel, the super-smart, disturbingly cute (to ginger fans) entrepreneur who created PayPal in 2002 with his friend Elon Musk and two years later loaned Mark Zuckerberg half a million dollars to crank up Facebook. Thiel turns out to be, among other things, a devout gay Christian, a serious Ayn Radian libertarian, and an unapologetic Republican who voted for John McCain in 2008. The mind boggles. It is clear that Packer, one of the New Yorker’s hotshot reporters these days, is both intrigued and appalled by Thiel and his friends. He’s invited to a dinner party where “the two subjects of conversation were the superiority of entrepreneurship and the worthless of higher education.”

[Biotech specialist Luke] Nosek argued that the best entrepreneurs devoted their lives to a single idea. Founders Fund [an investment group co-founded by Thiel with Napster’s Sean Parker] backed these visionaries and kept them in charge of their own companies, protecting them from the meddling of other venture capitalists, who were prone to replacing them with plodding executives.

Thiel picked up the theme. There were four places in America where ambitious young people traditionally went, he said: New York, Washington, Los Angeles, and Silicon Valley. The first three were used up; Wall Street lost its allure after the financial crisis. Only Silicon Valley still attracted young people with big dreams — though their ideas had sometimes already been snuffed out by higher education. The Thiel Fellowships [which award 20 $100,000 two-year grants to brilliant people under the age of 20 to enable them to quit college and start up business] would help ambitious young talents change the world before they could be numbed by the establishment.

I suggested that there was something to be gained from staying in school, reading great works of literature and philosophy, and arguing about ideas with people who have different views. After all, this had been the education of Peter Thiel. In The Diversity Myth,” he and Sacks wrote, “The antidote to the multiculture is civilization.” I didn’t disagree. Wasn’t the world of liberatarian entrepreneurs one more self-enclosed cell of identity politics?

Around the table, the response was swift and negative. [Artificial-intelligence researcher Eliezer] Yudowsky reported that he was having a “visceral reaction” to what I’d said about great books. Nosek was visibly upset: in high school, in Illinois, he had failed an English class because the teacher had said that he couldn’t write. If something like the Thiel Fellowships had existed, he and others like him could have been spared a lot of pain.

Thiel was smiling at the turn the conversation had taken. Then he pushed back his chair. “Most dinners go on too long or not long enough,” he said.

The third innovator featured is the 28-year-old French artist who goes by the initial JR, who has orchestrated large-scale guerrilla photo installations in the slums of Southern Sudan, Kenya, Cambodia, India, and Brazil. Raffi Khatchadourian’s article follows him as he creates an art project empowering regular people in the Hunts Point neighborhood of the Bronx.

Then there’s Ariel Levy’s piece on Rita Jenrette, former Congressman’s wife now turned Italian principessa — nutty piece but worth reading just because Levy is such a fine, entertaining writer.

While I’m at it, I want to mention a couple of pieces from last week’s Food Issue worth going back and reading. First and foremost is Eric Idle’s hilarious Shouts & Murmurs piece, “Who Wrote Shakespeare?” There’s also a fascinating piece by John Seabrook about apples, specifically the breeding of a new hybrid apple called the SweeTango. And Judith Thurman contributes a delicious and inspiring little meditation on pine nuts.