Cultural weekend! Friday night, Andy and I met friends for dinner at The Smith in the East Village in honor of a recently departed college chum. It was Hallo-weekend and the streets were full of costumed revelers. We were most amused to see a couple dressed as tourist (him in I ❤️ NY t-shirt) and the Statue of Liberty.

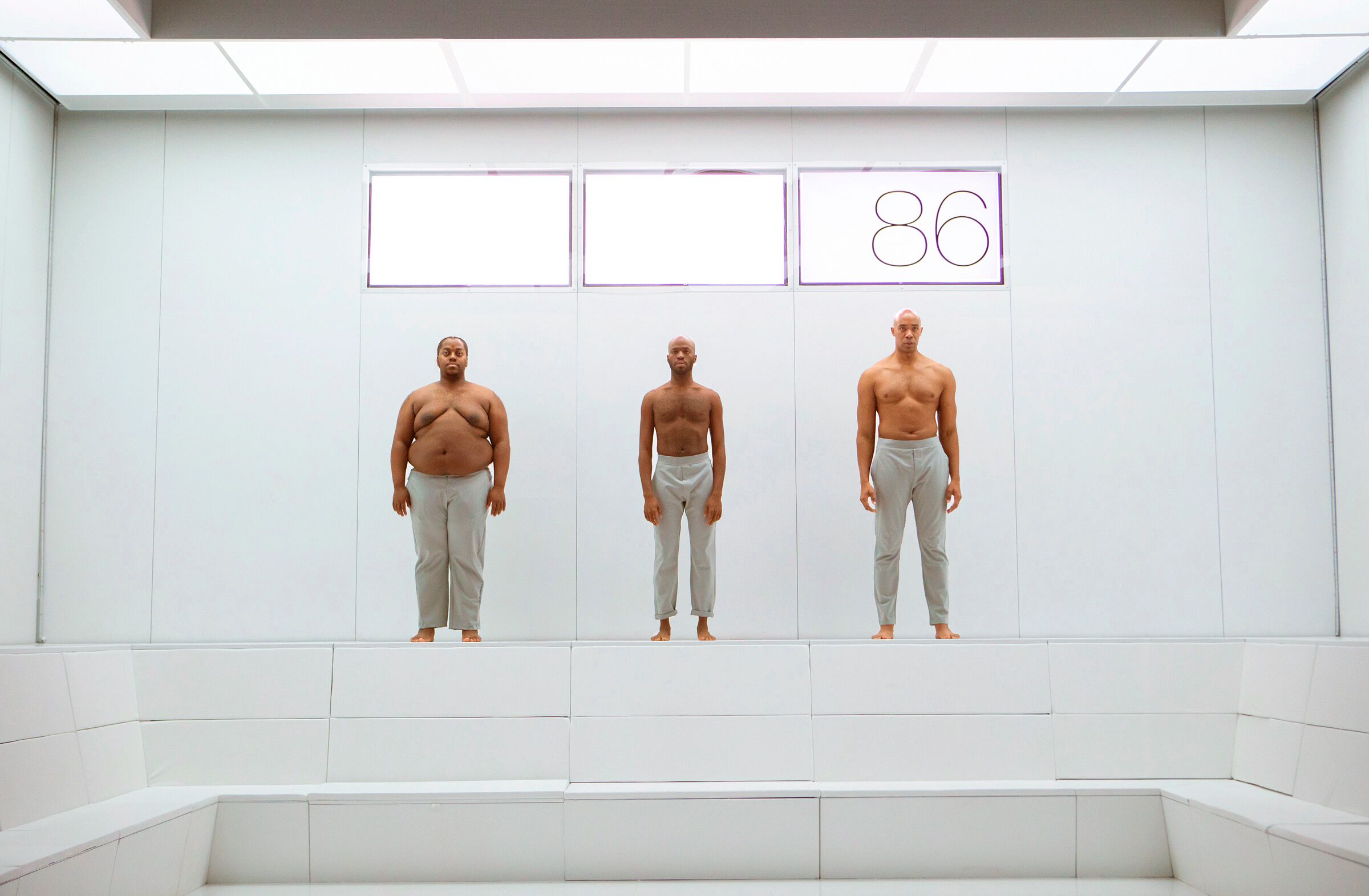

Saturday – beautiful day, up to 80 degrees. We took part in the Gays Against Guns action in response to the mass shootings in Lewiston, ME. I had a Google Hangout conversation with Alastair Curtis, a young theater artist in London who’s just discovered the work of Harry Kondoleon and wanted to talk to me in preparation for a reading he’s doing of Christmas on Mars. In the evening, Andy and I were back in the East Village to see Helen., the SuperGeographics production of Caitlin George’s play directed by Violeta Picayo. In the lobby we chatted a little with producer Anne Hamburger (whose En Garde Arts brought the show to La Mama), Linda Chapman, Chay Yew (looking very buff), and two young artists Anne is cultivating. I enjoyed the play, a dense, poetic, cheeky, queer/feminist riff on Greek mythology that reminded me of Young Jean Lee’s Lear the way it played fast and loose with familiar stories. In this version, Helen and her twin sister (!) Klaitemnestra and their sibling Timandra operate under the supervision of Elis, god of discord. This restless Helen isn’t waiting around to be abducted from her husband – she’s got wanderlust and knows how to use it. Picayo’s excellent production – light, fun, funny – made extensive use of quirky props (crowns, marbles, a barbecue) and almost continuous underscoring (by the great sound designer Darron L. West) with terrific performances, especially by charismatic Constance Strickland as Eris and Lanxing Fu as Helen (below center, with Grace Bernardo as Klaitemnestra and Melissa Coleman-Reed as Timandra).

Sunday afternoon we saw Sabbath’s Theater, Philip Roth’s late novel adapted for the stage by John Turturro with Ariel Levy. I never read the novel but the promotional material and the advance feature in the New York Times built up my expectations for a sexier/ filthier event than the New Group production turned out to be. But I guess for some (straight?) people any reference to masturbation comes off as racy rather than (as Roth has always demonstrated) a typical feature of most people’s sex lives. For all its lustiness, the play is primarily a melancholy contemplation of loss, desire, and death as the title character Sabbath (played by the brave, inventively comic, ever-watchable Turturro, below), a former puppeteer brought down by arthritis and a sex-with-student scandal, recalls the lovers, friends, and relatives he’s lost and considers joining them by throwing himself out the window of his high-rise apartment or walking naked into the sea. Jason Kravits and the great Elizabeth Marvel have fun playing all the other characters with distinctly different costumes, voices, and body habitus. Jo Bonney’s production struck me as tame, and in contrast to Helen., the sound score (by Mikaal Sulaiman) came off as intrusive and annoying at times rather than evocative or scene-setting. I pointed out to Andy that the fine-print trigger warning in the program (“This production contains nudity, sexual situations, strong and graphic language, and discussion of suicide.”) could apply to virtually every show at the New Group.

photo by Jeenah Moon for the New York Times

I loved Rob Weinert-Kendt’s succinct summary: “If Robert Altman directed a Chekhov play about a 1970s rock band struggling to perfect their next album, it might look (and sound) something like David Adjmi’s STEREOPHONIC.” I saw the play a couple of weeks ago and it’s stuck with me like few plays I’ve seen in recent years. A three-hour play can seem a little daunting these days, but Daniel Aukin’s production at Playwrights Horizons casts a spell. When I try to name the unusually evocative atmosphere to myself, I keep coming back to Fassbinder – the intense attention to tiny increments of human behavior, the honesty about intertwined love and depravity, artists at work, extraordinary design on every level, occasional longeurs but that being part of the astonishing success of capturing life in its complexity. Pop music was my first love, and I related to the play’s deep immersion in rock music culture much the same as Todd London did in his terrific essay on the PH website. (There you can also read commentary by David Byrne, who happened to be in the audience for the performance I attended; my friends and I noted how remarkably friendly and chatty Byrne was with the people sitting around him. One member of my posse is a hardcore Fleetwood Mac nerd and regaled us at intermission and afterwards with all of his observations about the Easter eggs hidden throughout the play – for instance, that Lindsay Buckingham has a brother who’s an Olympic swimmer, like the LB character in the play. And he knew exactly which Steve Nicks song was deemed too long to be included on Rumours.) The set designed by David Zinn manages to look completely natural and lived-in while being actually insanely meticulous in its creation of an artificial environment that works as an additional character in the play. Ditto the impossibly intricate sound design by Ryan Rumery. The performers are uniformly excellent, all playing their own instruments on ingenious original songs by Will Butler of the Arcade Fire. But what impressed me most of all is how the playwright, the director, and Tom Pecinka, the actor who plays Peter (the Lindsay Buckingham stand-in), collaborated to create the most nuanced and compassionate portrait of a perfectionist I’ve seen in any medium.