February 18 – I’ve been on the Sam Shepard beat for thirty years now, and every time I think it’s time to take a break, the universe sends me a different message. I thought I could live my whole life without ever seeing A Lie of the Mind again, and then I woke up the other morning absolutely convinced that I had to see the New Group’s revival directed by Ethan Hawke with a hot cast including Josh Hamilton, Laurie Metcalf, Marin Ireland, Karen Young, and Keith Carradine. Minutes later, I got an e-mail from my friend Richard inviting me at the last minute to the opening night performance (he’d won tickets at a fundraiser for the New Group, whose executive director Geoff Rich is an old friend of his). And the seats turned out to be front row center – an almost overwhelming vantage point from which to study not only the spectacle of hairy-chested Alessandro Nivola in boxer shorts (where is After Dark magazine just when you need it?) but also Hawke’s carefully rethought, re-imagined, and beautifully performed production of a problematic Shepard play.

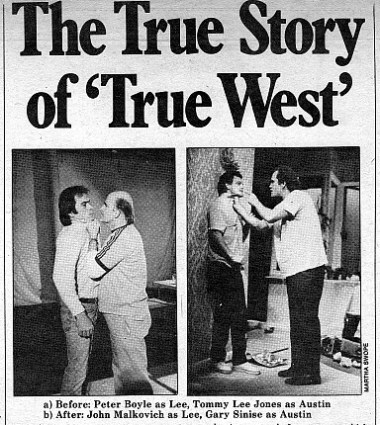

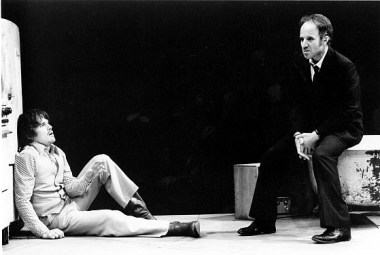

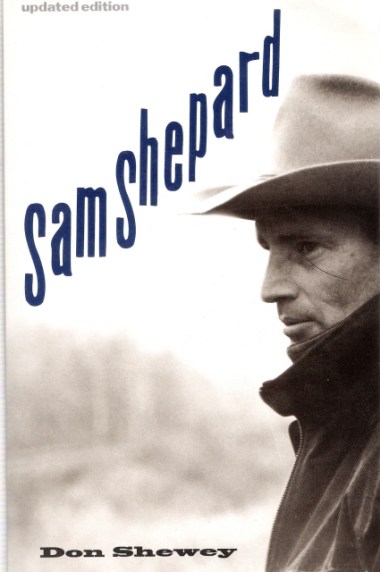

The 1985 original production of A Lie of the Mind is one of those legendary star-studded New York shows. Shepard himself directed an unbelievable cast: Harvey Keitel, Amanda Plummer, Geraldine Page, Aidan Quinn, Will Patton, Ann Wedgeworth, Jim Gammon, and Karen Young. The show was four hours long, with lots of live music by a bluegrass band, the Red Clay Ramblers. Unlike Ben Brantley, whose rave review of the New Group production declared it a “masterwork,” I thought it was a little ponderous and self-consciously epic. Having just written my Shepard biography (the book party was held in the lobby of the Promenade Theater, where A Lie of the Mind was playing), it was hard for me to see the play as anything other than a sequel to his four previous, more than semi-autobiographical plays (Curse of the Starving Class, Buried Child, True West, and Fool for Love). The previous plays had lots of merit as free-standing entities. In A Lie of the Mind, at least when it opened, the lines between imagination and autobiography were especially blurry because Shepard’s celebrity had suddenly pushed his personal life in public consciousness. He’d famously hooked up with Jessica Lange on the set of Frances, and he left his wife and 10-year-old son to live with her. The agony of that situation clearly propelled the writing of A Lie of the Mind, which opens with Jake calling his brother Frankie to say he’d just beaten his wife Beth to death (it’s easy to understand how the guilty party in a divorce might feel that way).

Ethan Hawke has a long history with Shepard: he was in Steppenwolf’s 1995 production of Buried Child in Chicago directed by Gary Sinise, Shepard played Hamlet’s father in Michael Almereyda’s fascinating film of Hamlet with Hawke in the title role (Shepard brought tears to my eyes when he pulled his son into his arms and growled into his ear “Remember me!”), and Hawke played one of the two leads in the New York premiere of The Late Henry Moss (see below, in the role originally played in San Francisco by Sean Penn). A whole generation younger than Shepard (he is, in fact, the same age as Shepard’s first-born son, Jesse), Hawke rounded up a posse of actors like himself who tread back and forth from theater to indie film with occasional forays into mainstream movies and TV.

From the get-go, his production departs from Shepard’s. First of all, he cut out almost all music except for underscoring and occasional bursts of song provided by Latham and Shelby Gaines, playing on homemade sound sculptures from a cubbyhole visible to the audience stage left. And instead of two separate areas floating in space, Jake’s family and Beth’s family occupy the same resolutely indoor set, fantastically crammed floor to ceiling with dusty old wooden drawers and boxes and family baggage. It looks like a cross between my grandparents’ farmhouse (I come from exactly the same kind of Midwestern white-trash family Shepard did) and I Am My Own Wife.

I understand that Shepard took one look at the set and declared “You ruined the play.” He was wrong. To my mind, Hawke and his cast have rescued the play by applying a vast amount of attention to the specifics of each character and each scene in such a way that, paradoxically, they open out into something much bigger and broader. For one thing, there’s no pretense that these folks are normal, psychologically stable individuals. They’re all quite out of their minds, in one way or another. Beth’s mother Meg and Jake’s mother Lorraine pretend not to know that their kids are married to each other. Even though Jake has indeed beaten Beth up badly enough for her to sustain brain damage, she clearly had more than a few screws loose beforehand. The way she attaches to Frankie when he comes to check up on her tells us a lot about her boundarylessness (and her love-starved relationship with her father). And especially in Nivola’s riveting performance, we see Jake’s violence as a highly unstable, combustible compound of genetics, alcoholism, wounded masculinity, love, fear, and blazing self-ignorance.

I could talk at length about each scene, each character, and each performance, but I don’t have all day so I’ll just hit the high points.

1. Although Shepard pooh-poohs psychological reality, the psychotherapist in me can’t help identifying the impact of trauma on both Jake and Beth. One lie in Jake’s mind is that he’s killed Beth, but that’s a strange displacement of his guilt about his participation in his father’s death, which he’s buried so deep that he doesn’t remember it. It only surfaces as a seizure that takes over his body, although he tries to articulate it in a scene that Nivola plays with terrifying clarity, when he says, “There’s this thing – this thing in my head…A scream from a voice I don’t know. Or a voice I knew once but now it’s changed. It doesn’t know me either. Now. I used to but not now. I’ve scared it into a different form.” In other plays (such as The Unseen Hand), Shepard has dramatized this phenomenon in almost science-fiction terms. And I know from my research that this self-alienation relates philosophically to the Gurdjieff work that Shepard has studied deeply. But Nivola plays it in a fantastically visceral, emotionally immediate way.

2. The mothers in a lot of ways seem like the same character – the same paradoxically ditsy and down-to-earth woman, paradoxically scornful of men and ferociously attached to them. I found it touching to watch how these actresses pulled that off – Young’s Lorraine infantilizes Jake like some textbook bad mother, completely unruffled by his bad behavior (as above — she’s seen it all her life and pretty much expects it) and Metcalf’s Meg doggedly serves her neglectful husband — without any extra commentary.

3. I found some moments of the performance unexpectedly personal and shocking. In the first scene with Jake and Frankie, during Jake’s frenzied temper tantrum Frankie instinctively knows to go stand in a corner and avoid eye contact, which certainly matches my experience of living with a raging alcoholic madman. My father, like Shepard’s, was a military man (and drunk) who died in 1996. He was still alive when I first saw the play, whose first act ended with the beautiful and touching image of Jake blowing his father’s ashes into the air. This time around, as soon as that scene began, I kinda lost it and watched the rest of it through tears of re-living my own father’s funeral — being presented with the American flag by uniformed riflemen, handling the box of ashes, the whole bit. Surprisingly powerful.

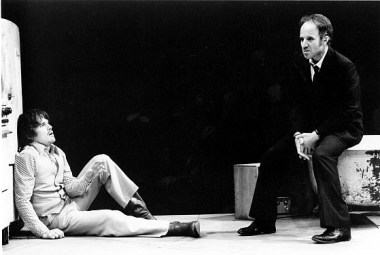

4. The romantic triangle and the family dramas that drive A Lie of the Mind speak to virtually anybody, but close followers of Shepard’s work will inevitably see the connections to his other plays. I was very impressed with the specific ways Hawke conjured the creepy, claustrophobic, murky tone of Buried Child – the set is very important in that way, but also the way Frankie spends most of the play stretched out on the sofa echoes the succession of lame (and lame-brained) men who occupy that position throughout Buried Child (and lower-class middle American life – as Sandra Bernhard would say, “the picture Norman Rockwell forgot to paint”).

And I was amazed to see the way he conjured Fool for Love in the unmistakably erotic tension between Jake and his sister Sally. That did NOT exist in the original production. Karen Young, in the role of Sally, had zero sexual energy. (A little gossip: Rebecca DeMornay was originally cast in the role, but after Jessica Lange walked into a dressing room and caught her with Shepard, DeMornay was gone, and Karen Young took her place. Young’s blank sexuality works a lot better in the role of Lorraine, even though she seems quite a bit too young for the part.) Maggie Siff has taken shit in the blogosphere for her supposedly weak performance in this show. I completely disagree. She comes in with a different energy from the others in a way that recollects Shelley in Buried Child, fittingly. She is a terrific match for Nivola’s scary/sexy energy. Plus, the two of them are so fucking hot I was afraid/hopeful that they would have sex right in front of me. (Or with me.)

And I was amazed to see the way he conjured Fool for Love in the unmistakably erotic tension between Jake and his sister Sally. That did NOT exist in the original production. Karen Young, in the role of Sally, had zero sexual energy. (A little gossip: Rebecca DeMornay was originally cast in the role, but after Jessica Lange walked into a dressing room and caught her with Shepard, DeMornay was gone, and Karen Young took her place. Young’s blank sexuality works a lot better in the role of Lorraine, even though she seems quite a bit too young for the part.) Maggie Siff has taken shit in the blogosphere for her supposedly weak performance in this show. I completely disagree. She comes in with a different energy from the others in a way that recollects Shelley in Buried Child, fittingly. She is a terrific match for Nivola’s scary/sexy energy. Plus, the two of them are so fucking hot I was afraid/hopeful that they would have sex right in front of me. (Or with me.)

5. Some other echoes of the Shepard canon: in the original production, Meg and Baylor folded up the American flag in a very simple way that communicated both domestic familiarity and unquestioned patriotism. Since then, Shepard wrote a whole play basically decrying post-9/11 flag-mania (The God of Hell) so Hawke shrewdly plays the scene for a few different flavors, including one pointedly stylized moment where they’re holding the flag fully open behind Jake, who says “Everything lies!” We seem to be in a moment of political commentary…and then it’s dropped. Which I think is cool and preserves the several mysterious undercurrents of the play. And at the very end of the play, having the oilcan of Lorraine’s family memorabilia burning in the same room where Meg is looking out the window to see “a fire in the snow” conjures the inside/outside speech of Action, one of my favorite early Shepard plays.

6. With this kind of omnibus set, lighting is crucial. Designer Jeff Crotter does a fantastic job of using light to define, slice up, isolate sections of the stage to create the simultaneity of time and place that is part of the quirky magic of Shepard’s plays.

7. A few quibbles. Shepard plays fast and loose with naturalistic action in this play. Still, in this production Beth seemed to move with amazing swiftness from not being able to stand up straight to lap-dancing with Frankie on the sofa. I’m a huge admirer of Josh Hamilton, who played Frankie, and he does a terrific job here, though sometimes that leg injury seemed to come and go. And during the whole weird scene when Beth’s brother Mike (a pretty thankless role, reasonably fired up by Frank Whaley) drags Jake into the house with a rope around his neck, Laurie Metcalf has to lie on the floor conked out, pretending to be invisible. I felt a little sorry for her in that moment. Otherwise, Metcalf was nonstop brilliant. The one cast member who didn’t do it for me was Keith Carradine as Baylor. All the other actors succeeded in suspending my memories of the original cast, but Jim Gammon was completely believable as a crusty old pig-headed hunter with feet so gnarly and calloused that he needed to rub them with mink oil. Carradine – no way.

Opening night was predictably buzzy, attended by the New Group in-gang: Wally Shawn and Debby Eisenberg, David Cale, Matthew Broderick, etc. I chatted with Scott Elliott, who’s about to go into rehearsal with the musical of The Kid, Dan Savage’s book about gay parenting. There was a party afterwards at Montenegro, a new restaurant in the NY Times building. I was happy to run into Emily McDonnell, who was in Wally’s play Grasses of a Thousand Colours in London. And I was amazed to see that Sylvia Miles is still around a kicking and going to opening-night parties.