December 17 – A whole gang of us posse-fied to see Tamar Rogoff’s Diagnosis of a Faun at La Mama, stoked by the New York Times feature about the making of the piece. The choreographer used a good chunk of her Guggenheim fellowship to spend several months working with Gregg Mozgala, an actor with cerebral palsy, exploring ways for him to expand his physical capacity and to make creative uses of his bodily limitations. The piece they created together wittily and poignantly expands beyond the novelty of watching a guy with CP dance to contemplating the essence of dance, movement, our bodies, how we feel about them, what we do with them. The show told a loose tale about two doctors presenting their research based on treating two different individuals, one an injured ballet dancer (Lucie Baker) and the other one a mythological faun (Mozgala, above). The doctors, who both spoke and danced, were played by modern dancer Emily Pope-Blackman and Donald Kollisch, who is a real middle-aged M.D. with no dance training. (In the talkback afterwards, Rogoff mentioned that growing up with a doctor father gave her an appreciation for medical language, so she used a lot of it in this piece.) Having Mozgala play a faun – a satyr-like horned creature with a human upper body and a hoofed lower body – was a brilliant stroke, funny and fascinating, and it gave Rogoff a few different jumping off points, including the famous Nijinsky ballet to Debussy’s “Afternoon of a Faun.” The piece was only 65 minutes but it still felt 20 minutes too long, as the choreographer dutifully came up with duets for each pair of performers. But we enjoyed talking about it over dinner at Counter in the East Village.

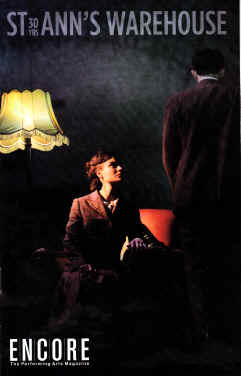

December 27 – I was psyched to see Kneehigh Theatre’s stage production of Brief Encounter at St. Ann’s Warehouse because I only recently saw David Lean’s masterful 1945 film starring Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard, a triumph of romantic neo-realist cinema based on an extraordinarily deft play (originally titled Still Life) by Noel Coward. That may not have been the best preparation for the stage production, for which adaptor-director Emma Rice has wrapped the play in a dozen music-hall numbers and tons of broadly comic business, as if not trusting that the audience would sit still for the understated drama of two married people conducting a chaste, short-lived but life-changing love affair. I liked that in her program note, Rice makes an explicit connection between Coward’s homosexuality and the portrayal of a doomed “secret love.” But I thought virtually everything about the show was overplayed, cutesy, annoying, including the central performances by Hallah Yelland as Laura and Tristan Sturrock as Alec. In the last couple of scenes, as their sad parting draws near, the show does tone down the Must-Keep-the-Crowd-Entertained-at-All-Times shtick, and the final scene does pack its restrained, heartbreaking punch. (You can watch the film version of the scene here.) I recognized Rice’s efforts to use the tools of theater (including music, sound, projections, and actors moving through the audience) to bring the story closer, and there was a clever use of having actors step through the movie screen into the movie. The production was similar in many ways to Matthew Bourne’s zippy, thrilling staging of The Servant at BAM a couple of years ago – which I liked much better – and bore a family resemblance to Katie Mitchell’s staging of The Waves last year – which I detested. I guess I’m allergic to shows that are so heavily calculated toward crowd-pleasing. But the crowd was quite pleased. Andy certainly liked the show much better than I did, was dazzled by the multimedia storytelling and especially enjoyed the video projections (the sequence of champagne bubbles turning into stars in the night sky, for instance, which was spiffy).

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.