March 3 – I’m in awe of Martin McDonagh as a playwright for his humor, for his theatricality, for his sly storytelling, and for his sheer mastery at composing sentences that explode in the air. His new play, A Behanding in Spokane, had me from the very beginning and never lost me. First of all, there’s Christopher Walken with his wild hair and ruined face, sitting on the bed in a crappy hotel room with one hand and one stump, looking grim. That gets a laugh all by itself, somehow. The flimsy latticed wardrobe door starts rattling, being kicked by someone apparently bound and gagged inside. That gets a laugh. (The crappy hotel room is beautifully designed by Scott Pask: the wardrobe has been built as an afterthought to the room, without any attention to the wallpaper pattern.) Walken goes to the wardrobe, opens the door, leans in and fires two shots. That gets a laugh. He closes the door, walks over to the phone, dials a number, and speaks the first line of the play: “Hi, Mom.” Laugh. This insane mixture of menace, goofiness, surprise, and mundanity – the essence of McDonagh’s dramatic universe – may not be everybody’s cup of tea but it’s absolutely mine.

The play occupies a territory midway between David Mamet and Sam Shepard. Like American Buffalo, the play is a caper that involves bumbling low-level thieves, terse sentences, and fast-flying obscenities. Walken’s character, Carmichael, has spent the last 47 years trying to retrieve the hand that a gang of hillbillies chopped off when he was 11 years old. Somehow he ends up in small-town Arizona (?) where two young dumbass pot dealers (Toby and Marilyn, played by Anthony Mackie and Zoe Kazan) claim to know where they can get his hand for $500. There’s always been a strong connection to Shepard in McDonagh’s plays – as here, at the center is a showdown between two guys who are more or less alter-egos, and there’s a wittily self-conscious theatricality afoot. Carmichael’s unlikely sparring partner is Mervyn (played by Sam Rockwell), the guy who works at the front desk of the hotel. Mervyn, who is quick to insist that he’s NOT “the receptionist” and was apparently doing sit-ups in his boxer shorts when Carmichael arrived to rent the room, is the play’s Fool, meaning he seems like a loser but winds up being the voice of truth and reason, sort of. He’s both a character and a device, the picture pointing to the frame, the writer talking to himself and punching holes in his own story.

The plot is very slight and not especially plausible, but key moments tell us to let go of naturalistic drama and pay attention to McDonagh’s postmodern hijinks. Mervyn first appears at the door to inquire about the gunshots he heard, and after repeating back the ludicrous explanation Carmichael gives him he asks, “Where is this story going to go?” Carmichael says, “We’ll find out as soon as you leave the room.” And although it wouldn’t seem too hard for two energetic kids to run away from a one-handed man, even if the other hand was holding a gun, all Carmichael has to do is whistle and jerk his head and his two captives willingly walk across the room to be handcuffed to heating ducts, as if under a spell. There’s no intermission, but the action is interrupted by an interlude in front of a drawn curtain in which Mervyn steps out to give us his hilariously discursive back-story. It’s a kind of vaudevillean moment that contributes to lifting the play out of the kitchen sink and conjures both Beckett and Brecht. And the scene is written and played in a manner very close to the bravura letter-reading monologue in The Beauty Queen of Leenane, the play that introduced us to Martin McDonagh.

Directed by John Crowley, the cast is spectacular – David Zinn called it “the character-actor Olympics,” although as he pointed out, the roles of the two kids are so thinly drawn that you end up feeling sorry for the actors, especially Anthony Mackie, an excellent actor (see him in The Hurt Locker!) who has to spend most of the show playing a stoopid guy with vocabulary that ranges from “motherfuckin’ this” to “motherfuckin’ that.” The New Yorker’s Hilton Als was enraged by the shallow stereotypical nature of the character and Carmichael’s casual racism, and DZ objected to Carmichael’s needling Toby for “crying like a fag.” Somehow those things didn’t bother me – I saw them as part of McDonagh’s edgy examination of theatrical language, which included Marilyn’s hilariously earnest/lame challenging Carmichael for his homophobia and his use of “the n-word.” If anything, I wound up thinking that Mackie and Kazan were miscast. They’re terrific actors, up-and-coming stars (in Ian Rickson’s production of The Seagull last year, she was the best Masha I’ve ever seen), but a little too squeaky-clean to really represent small-town losers. Christopher Walken is, of course, amazing – ceaselessly inventive, scary, present, vulnerable, and as DZ put it, he has the deadest deadpan on earth. I was knocked out by Sam Rockwell’s performance because he goes nose-to-nose with Walken and holds his own without budging, and his performance is a comic triumph of its own.

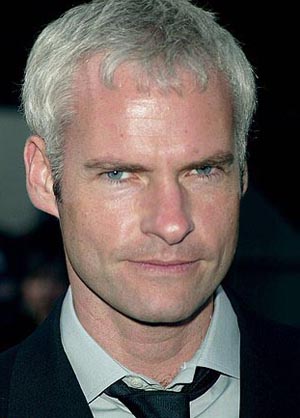

The show got mixed reviews – Ben Brantley in the Times called it “erratically enjoyable” – but then so did McDonagh’s debut as filmmaker, In Bruges, which I think is one of the funniest and best-written movies of the last decade. David was much cooler toward the play than I was, but we had a good juicy conversation about it over drinks at Angus McIndoe, where McDonagh apparently does all his interviews and post-show drinking. I didn’t see him there, but he was at the theater greeting well-wishers, and I got a kick out of seeing the silver fox in person (see above).

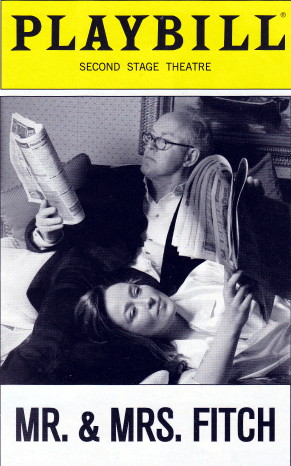

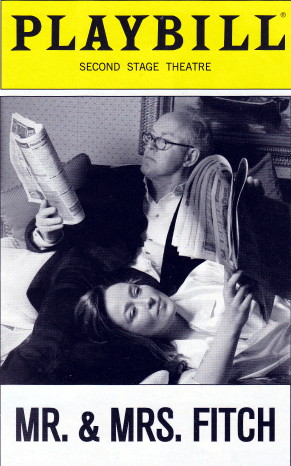

March 5 – DZ called Behanding “the slightest excuse to gather 1000 people in a room,” but that encomium is much more appropriate for Mr. & Mrs. Fitch at the Second Stage, Douglas Carter Beane’s hard-hitting satire about…celebrity journalism. In an attempt at Noel Coward-style brittle and topical comedy of manners, John Lithgow and Jennifer Ehle play gossip columnists who drop about 100 literary names to suggest that they’re superior to everybody else. But it’s thin, hasty stuff that recycles old jokes (“Bi now, gay later”) and dispenses with character continuity altogether (one minute She’s avidly encouraging Him to invent a fake celebrity – the play’s major plot point – and the next minute she’s castigating his journalistic ethics for doing so). The funniest idea is that headline writers at the New York Post use “Camptown Races” as the rhythmic model for their creations – you can tell they’ve hit on a classic if you can follow it with “doo-dah, doo-dah!”

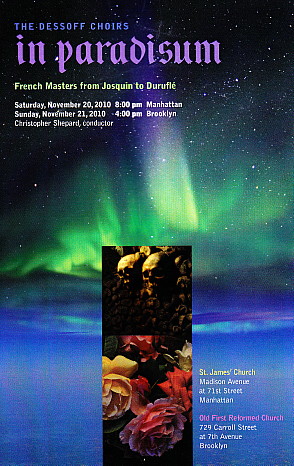

March 6 – Andy sings with the Dessoff Choirs, a volunteer group that symphony orchestras job in for massive choral works (like Britten’s War Requiem). Every so often they do a concert by themselves, and this program at Merkin Concert Hall consisted of three contemporary pieces: three Psalms by the recently deceased Lukas Foss, a pretentious and ugly piece by Harold Farberman called Talk inspired by dialogue overheard at an upstate diner, and Kyle Gann’s Transcendental Sonnets, based on a series of poems by Jones Very (1813-1880). The Foss and the Gann at least provided some beautifully lush choral singing, and the two soloists were excellent – tenor Jeffrey Hill and soprano Megan Taylor.