I just heard the news that Jim Strahs died October 1. He was an amazing, highly original writer who contributed texts to several Wooster Group pieces (most notably North Atlantic and the “Rig” section of Point Judith) and wrote a few hard-bitten novels, one of which — Wrong Guys — Mabou Mines adapted for the stage. I interviewed him for the Village Voice at the time that his novel Queer and Alone was published. My article was headlined “Not Rich and Not Famous,” which is accurate — but I want to say “Not Forgotten,” not by me anyway. Many of his works are available for free download from his website.

Archive for the 'R.I.P.' Category

R.I.P.: Jim Strahs

October 13, 2011R.I.P.: Crazy Owl

August 14, 2011A mailing from Short Mountain Sanctuary, the Radical Faerie enclave back in the hills of Tennessee, informs me of the passing of Charles Emerson Hall, aka Crazy Owl, whom I met briefly at the first Gay Spirit Visions conference in North Carolina in 1990 (see below) and perhaps one or two other occasions when I was communing regularly with the faeries.

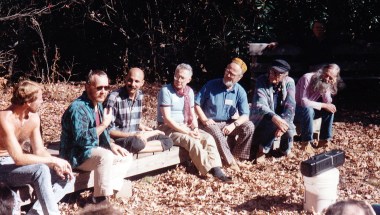

left to right: Steve Greer, Franklin Abbott, Andrew Ramer, Ron Lambe, John Burnside, Harry Hay, Crazy Owl

This unsigned remembrance from the Short Mountain Goatzette offers a peek into a realm that I treasure, even if I encounter it seldom in my life these days:

“Crazy Owl, boyish beauty and land lover, passed away on April the 4th of this year. His body was laid to rest in the green hillside of the Barefoot Farmer in whom he found companionship and kin.

“Crazy Owl began his healing work in psychotherapy in Massachusetts, yet his work in statistics caused him to radically shift his priorities to the land. Crazy Owl returned to his childhood love of the land, entymology, botany, and bare bottomed hiking among his many passions, taking on a bold quest of learning traditional Chinese medical approach and integrating that wisdom into the world growing around him. Fostering communities near Atlanta and carrying this tradition on wild Missionary Delight tours, the wisdom of this walker of the wild brought hope and healing with mischief while finding welcome in many communities. His pilgrimages to Serpent Mound evoked the spirit of community and tribe while demonstrating that he had found a sustainable path in reconciliation with his whiteness and privilege.

“Many stewards receiving this letter come to Short Mountain for the herbal wisdom walks that the barred Owl facilitated at gatherings. Perhaps the statistician kept a record of the many lives he touched yet surely the number is great. The stories that live on in remembrance of Crazy Owl continue to inspire all those seeking a radical way of life.

“The body loving, sex positive liberation movement generated by Crazy Owl is remembered in his written legacy, including an illustrated book. Coming Out by Chuck Hall is a piece on the subject of coming out, expanding its definition to include body love, sharing love, self love and self acceptance.

“Those with access to the net interested to find out more about this fascinating man can visit his website: http://crazyowlsperch.com.”

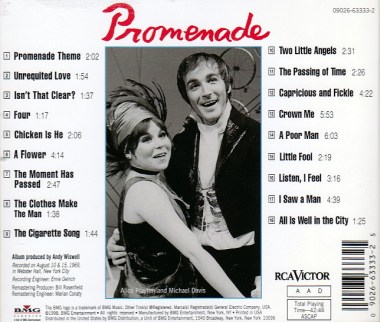

R.I.P.: Alice Playten

June 27, 2011The morning after the good news from Albany declaring same-sex marriage to be legal in New York State, the sad news arrived that Alice Playten died at age 63. Alice was one of those performers who wasn’t necessarily a household name for most Americans but was absolutely legendary and beloved in certain pockets of New York theater as a comic actress and singer. Her resume came loaded with classy credits: after making her stage debut at the Metropolitan Opera in Wozzeck at age 11, she appeared in the original productions of a bunch of famous musicals, from Broadway classics (Gypsy, Hello, Dolly!) to Off-Broadway landmarks (from Al Carmines and Irene Fornes’s Promenade to Tony Kushner and Jeanine Tesori’s Caroline or Change).

Funnily enough, I first encountered Alice as a comic spoken-word presence on Martin Mull’s 1977 album I’m Everyone I Ever Loved. I moved to New York in 1980 and commenced a long-term relationship with Stephen Holden, who knew Alice slightly through the music business and had adored her crazed performance in National Lampoon’s Lemmings Off-Broadway. When I met her and her husband Josh White (of the famed Joshua Light Show), we hit it off like gangbusters.

The four of us became very good friends, spending many birthdays and holidays together, bonding over our love of good theater, good music, good movies, and good laughs.

It was fun going to see shows with Alice because she was an enthusiastic theater- and concert-goer with very discerning tastes. She liked to love things and often had extremely nuanced appreciations (especially of song lyrics) but she wasn’t a pushover and called out performances whose quality was sub-par. (I remember her remarking of one male stage star’s performance on Broadway, “That was so hammy I could smell the pineapple!”) She was very plugged-in, loved being in the know, dishing the dish and sharing show-biz gossip — less about who was an asshole and who did what to whom but more about what exciting projects by excellent artists were coming down the pipeline.

Alice would have been perfectly content working in theater or movies 52 weeks a year but like many great performers didn’t work as much as she would have wanted to. Knowing her meant getting a peek inside the life of an actor whom everybody in the theater knows but who still spent way too much time waiting for the phone to ring with the next job. I have very fond memories seeing her at Playwrights Horizons in Mark O’Donnell’s hilarious That’s It, Folks! and many times in Caroline or Change, first at the Public Theater and then on Broadway. And I remember what a big deal it was for her to be cast in Ridley Scott’s fantasy film Legend, which starred a quite young Tom Cruise.

After Stephen and I broke up in 1993, some of our friends felt the need to take sides, and Stephen got Alice and Josh in the divorce. After that, they were cordial to me but not close. But I wished them well and cherish the times we spent together. Through thick and thin, enduring many ups and downs, Josh was the epitome of a devoted partner to Alice, and I share with him both the sadness of her passing and the many joys of having known her.

R.I.P.: Doric Wilson

May 10, 2011Doric Wilson, who died Saturday May 7 at the age of 72, was virtually unknown to mainstream America, even to most theater people. But within the world of Off-Off-Broadway and post-Stonewall gay theater, he was a pioneer. He was one of the young out gay playwrights who made the legendary Caffe Cino his artistic home in the 1960s (along with Lanford Wilson and Robert Patrick), and in 1974 he founded the first gay theater in the United States, The Other Side of Silence (TOSOS). He had a tremendous influence on me as a young theater critic and baby gay liberationist hungry for historical touchstones.

We met in the summer of 1976, when I interviewed him and John Glines (separately) for a series of articles about gay theater for Boston’s Gay Community News. I was an earnest, starry-eyed 22-year-old Boston University student at the time, and I ended up publishing a rambling Q&A with Doric in GCN that strikes me now as embarrassingly naïve. But it was true that, as I wrote in the introduction, “As a person, Wilson is not ‘sort of’ anything – he is extremely intelligent, well-read, opinionated, headstrong, garrulous, and energetic.” Among the things that impressed me about Doric was his outspoken critique of gay homophobia, his willingness to describe himself unapologetically as “very promiscuous,” his openness as a leatherman, his refusal to distance himself from gay bar culture, and his frankness in articulating the subliminal ways that sexual attractiveness affects the way people interact professionally.

I don’t think anyone in the press had ever paid such close attention to Doric. I think he was flattered by my attention, as I was flattered by his openness (and his flirtatiousness, which led to the inevitable and inevitably anticlimactic one-night stand). Every time I saw him after that, he went right back into lengthy expostulation, as if I were still interviewing him, as if I were his personal historian, which was a little bit charming at first but quickly grew wearying. For all I know he did that with everyone. A large man physically and energetically, Doric spoke with a resonant, commanding voice as if addressing the multitudes, even in intimate circumstances.

In some ways, I was glad to take on the mantle of gay theater historian, because I had an ardent interest, particularly in the early days of Off-Off-Broadway. And I admired Doric’s plays (such as A Perfect Relationship and Forever After) for their willingness to depict the mundane aspects of gay life and romance with directness and humor as well as a sturdy but unpretentious theatricality. He liked to emulate the epigrammatic wit of Noel Coward but he also incorporated the casual way drag queens talk directly to the audience.

In 1977, I wrote a review of Doric’s play The West Street Gang for The Advocate, the national gay newsmagazine. (It was reprinted in Mark Thompson’s Long Road to Freedom: The Advocate History of the Gay and Lesbian Movement.) The play addressed the topical issue of gay-bashing and was performed site-specifically at the Spike, a leather bar in the West 20s, an area quite vulnerable to late-night attacks by marauding haters. Similarly, his play about the Stonewall uprising, Street Theater, premiered at the notorious Mineshaft and has a history of productions staged in funky gay bars. I was proud to include Street Theater in my anthology of gay and lesbian plays, Out Front, published in 1987 by Grove Press.

At a Queer Theater Conference in 1995, I moderated a panel discussion among several ground-breaking artists about the emergence of an out theater aesthetic. (A redacted transcript of this discussion appeared in The Queerest Art: Essays on Lesbian and Gay Theater, edited by Alisa Solomon and Framji Minwalla, who convened the conference for CLAGS.) Doric was the grand old man on the panel, and he spoke very personally about his background with details I had never encountered anywhere else:

“I came to New York in 1958 from a ranch in Washington State. I did not come to New York in the cowboy style of the seventies. In the fifties, if you came from a ranch in Washington State, you came to New York trying to look like Noel Coward, and I looked as much like Noel Coward as I could. I’ve always been out. I grew up in a sort of pioneer family in a very unpopulated pioneer country, at that time, in Washington, the Five Cities.

There weren’t any five cities when I grew up. There were only two cities. But my grandfather had more or less founded the county, and built the roads and what-have-you.

So, I had that wonderful old-time American arrogance of pioneers, that it didn’t matter what I did, nobody had a right to say anything to me. So I came out in school. I came out because a friend who was gay killed himself when he realized that he was about to be discovered, and I decided I wasn’t a good enough shot to kill myself, so I’d better come out…

I came to New York to be a set and costume designer, but I was so naïve, I had no idea where one studies set and costume design. So I was used as an actor. I did any number of stock productions of Auntie Mame as young Patrick Dennis. My roommate at the time was a straight English actor and I wrote a play for a little theater workshop that we were in, an Adam and Eve play called And He Made a Her.

An actress in that company had just done a Tennessee Williams play at this coffeehouse on Cornelia Street in the Village. Now those of you who know New York City and know Cornelia Street know that it runs for one block. In the early sixties, what is now the West Village was almost part of Little Italy. It was not part of Bohemia.

So, the Caffe Cino was really more in Little Italy environment than New Bohemia. This actress, Regina Oliver, took me down to the Cino, introduced me to this short, impish, round man behind the counter: Joe Cino, who always had one hand on the arm of the cappuccino machine or ringing a bell to start the performance, so I always see Joe Cino with one arm in the air. I started to hand him the play while he was making a sandwich and making cappuccino. He opened the notebook, and he said, “Three weeks from now, on Friday,” and closed the notebook and pushed the play away. I turned to Regina and said, “What does that mean?” She said, “That’s when you open.” From that point on, we all just did plays at the Cino. Lanford [Wilson], myself, Tom Eyen – we all wrote gay plays there, but it never occurred to us that’s what we were doing. We also wrote bad plays there. Joe was completely open.

The other side of the coin was critics. In the sixties it was a problem if you were known as an out gay playwright. There were theaters that would not do your work. The most important of them was the Public Theater. Most of the Cino playwrights were not done at the Public. But we had the Cino.”

R.I.P.: Phoebe Snow

April 26, 2011Sad news today about the death of the extraordinary pop-jazz singer Phoebe Snow.

Like many people, I loved her music since her first album, which came out in 1974. I saw her in concert once or twice in Boston, and then when I moved to New York City as a busy and ambitious freelance journalist, I interviewed her for an article for Rolling Stone. The story never ran, because the album the story was tied to got shelved. But I had hit it off really well with Phoebe, so I proposed to do a profile of her for Esquire. It was my first foray into long-form magazine journalism — I spent months researching and writing the piece, and it was a landmark for me. The article got a lot of attention. (You can read it online here.) It was the beginning of my long relationship with Adam Moss, who was still a junior editor at Esquire before becoming the wunderkind of the NYC magazine world. And I got to hang out with Phoebe Snow for hours and hours. She was really fun and funny, touching and vulnerable and not a little bit crazy. I would see her periodically over the years, socially and in concert. I was very sad to learn last year that she’d had a serious stroke, and today marks the end of an era.