7.3.99 — Central Park Summerstage is a free outdoor concert series where I’ve seen some hot shows over the years: Ani diFranco, Patti Smith, a collaboration between the Klezmatics and the Master Musicians of Jajouka, the annual Afrika Fete, etc. I don’t think any single concert in Central Park has turned me on as much as the one I saw the other night — “Joni’s Jazz,” a celebration of Joni Mitchell’s jazz period (from “Court and Spark” through “Mingus”). The advance word was that Vernon Reid, the guitarist and leader of the black rock band Living Colour, was assembling a great band with guest singers including Eric Anderson, Jon Hendricks and Annie Ross, John Kelly, Chaka Khan, P.M. Dawn, Duncan Sheik, and Jane Siberry — AND that they would be doing, among other things, the entire “Hejira”album from beginning to end. For a Joni-holic like me, this sounded irresistible. The concert was a benefit for Central Park Summerstage, so general admission tickets were $10, and seats in a special VIP section (in the bleachers, in the shade) were selling for $35. But I knew that Stephen Holden could get us good press seats for free so I talked him into going with me. He’s also a major Joni fan, and “Hejira” is one of his all-time favorite albums, but his feelings about Joni have cooled a bit since she complained in print about something he wrote about her in the New York Times. He was instrumental in shaming the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame into inducting Joni, and his article quoting her talking about searching for the daughter she gave up for adoption helped bring about Joni’s reunion with Kilauren — but still Joni griped that the stuff about her daughter was off the record, or some crazy bullshit. So now Stephen feels a little hurt that one of his idols is pissed off at him. Not enough to boycott “Joni’s Jazz,” though.

On the day of the concert, thunderstorms were predicted, and it rained all afternoon. Finally, the sun broke through just as we converged at the will-call booth set up outside the Rumsey Playfield, where the concerts take place. The concert was scheduled for 7:30, doors opened at 6:30, and I wanted to get there early to make sure we got good seats. So I packed a picnic basket of goodies to keep us entertained before the show. Long lines were already forming to get into the show, but Stephen’s press credentials earned us yellow wristbands, and when we flashed them to a staff member, he escorted us to the gate and pointed us to the press section, right in front of the stage. (Ah, the power of the press!) We selected choice seats on the center aisle in the sixth row — perfect seats! Just when it was seemingly like a perfect night for an outdoor concert, the wind blew some very dark clouds our way, and we had to huddle under umbrellas for a 20-minute rainshower. But you know how that is — bad weather at an outdoor concert bonds an audience even more. As if a Joni Mitchell cult audience needed any more bonding. I spied three Joni devotees that I know from the Radical Faeries — Ken Cooper, Dennis Burkhardt, and Jay Warren — who had been in the park all afternoon listening to the sound check. They’d been first in line, and for $10 they’d also scored prime seats just across the aisle. Ken was full of Joni gossip. He’d heard that Joni had called John Kelly (a performance artist who does a whole show in Joni drag called “Paved Paradise”) to ask what he would be performing. He told her “Amelia,” and she made a special request that he do “Shadows and Light” (a highlight of “Paved Paradise”). We also heard that Joni had been spotted backstage, and Ken commented how surprising it was that Joni would be here rather than with her daughter, who’s about to have to give birth herself. (Joni hounds always seem to know these things.)

Sure enough, moments before the concert began, a ripple of applause went through the audience as Joni entered and took a seat just two rows ahead of us, to our left. She smiled and waved and bowed to the audience, surprisingly eager to be acknowledged. She was accompanied by her handsome boyfriend and an older rock-manager type with a salt-and-pepper beard and a straw cowboy hat.

The show started with some official business. Central Park Summerstage producer Erica Ruben thanked all the corporate sponsors and brought out Parks Commissioner Henry Stern to welcome the crowd. In his official capacity, Stern made a brief nod in passing to Mayor Giuliani, which set off a huge round of booing from the audience. Stern started trying to defend the mayor, but when he saw he wasn’t going to win over this crowd he quickly introduced someone from the Canadian Consulate. The concert took place on July 1, also known as Canada Day, so the consulate paid for a lot of the expenses and plastered the joint with maple-leaf flags. Finally, Danny Kapillian took the stage. He’s the guy who dreamed up this event. He hogged the stage a little too long for everybody’s taste, but hey, he spent two years organizing the show, and this was his big moment. I actually got a little choked up, vicariously experiencing his dream-come-true moment. He made it a point to mention that the first time he ever saw Joni live was at Forest Hills Tennis Stadium around the time of the “Mingus” album, and he remembered that storm clouds hovered three inches above their heads for the whole concert — and then five minutes after the last encore it rained like the dickens. So he hoped that the weather gods would similarly bless “Joni’s Jazz.” And they did.

The music kicked off strong with “Trouble Child,” sung by Toshi Reagon. I remembered that Toshi had also been first up to bat at the Laura Nyro Memorial Concert at the Beacon Theater a couple of years ago (she sang “The Confession” and “Eli’s Coming”). Toshi is a big ol’ black dyke whose mother is Berenice Johnson Reagon, founder and leader of Sweet Honey in the Rock. She used to have Tracy Chapman-like dreads, but now she’s shaved her head, and she’s bigger and scarier looking than ever, almost a cartoon gangsta blob. But the girl can SANG, and the band (two guitarists, two drummers, two keyboardists, two or three winds, and three backup singers) rocked. It’s so rare to hear anyone else sing Joni’s songs, especially black singers, and the combo would be a revelation all night long. Next up, for instance, was a wild hard bop version of “The Jungle Line” sung by Dean Bowman and rapped by Carl Hancock Rux.

When Jane Siberry came out to do “People’s Parties,” it became clear that this show hadn’t been tightly rehearsed. She was reading the lyrics off a sheet of paper and still blew about half of them, and she kept smiling nervously in the direction of Joni herself, who looked displeased. (Everyone around Joni kept sneaking glances at her to get a minute-by-minute impression of her reactions to the show.) I was surprised at how untogether Jane Siberry was. Stephen speculated that Holly Cole, who canceled because she was sick, was scheduled to sing “People’s Parties” and Jane got roped in as a last-minute replacement — a good theory that seemed even more likely when that song segued into an instrumental version of “The Same Situation,” featuring the fabulous Ravi Coltrance on soprano sax.

One of the backup singers was Christina Wheeler, a rising star in the downtown Manhattan music scene whom I’d never seen. I couldn’t wait to hear her do Joni, but she bombed bigtime, overemoting her way through “Edith and the Kingpin” abrasive and off-pitch. (Daily News critic Jim Farber and his friend Claire, sitting a few seats away from us, dubbed this “the Gong Show version.”) She also screeched through “Jericho.” I felt sorry for her — she looked scared shitless.

Things picked up when Prince Be from PM Dawn came out to sing “Free Man in Paris.” He even got Joni going — I looked over and saw her singing along, which cracked me up for some reason. “Joni Mitchell don’t lie,” he said, quoting the Janet Jackson line that others would echo later in the evening. Prince Be’s a delightful big queen, and it seemed perfect for him to be singing a song Joni wrote about David Geffen. He had a DJ onstage who didn’t seem to be doing anything during the song. But then afterwards, Prince Be had the DJ play the little snippet “I’s a Mugging” from the “Mingus” album, and then he brought on a trio of rappers called the Mood Swingers who romped through a noisy rap to a sampled loop of “I’s a Mugging.” This was clearly a surprise to the producer, who stood offstage looking furious, but Vernon Reid and the band seemed to get a kick out of throwing in a hard-core rap interlude.

Chaka Khan swept onstage, of all people to do “Don’t Interrupt the Sorrow,” of all songs — but it turns out that Chaka and Joni are some version of homegirls. Chaka said, “When I meet girls who think they can sing, I tell them to get the ‘Hejira’ album and try to harmonize with THAT!” She apparently reveres Joni and knows her stuff inside and out. Selling the lyrics isn’t really her strong point — the nuances of a line like “Your notches, liberation doll” disappeared entirely, and Chaka later admitted that she had to go to the dictionary to find out what the word “quandary” meant — but the amazing thing about Chaka is that she found notes that you don’t hear Joni sing on the record. And every once in a while she just opens her mouth and lets out a big wild wail that’s as exciting as Aretha at her most inspired. Joni led a standing ovation for Chaka. [NB: you can hear this performance on YouTube here.]

Eric Anderson came out, well into his 50s and handsome as ever. He chatted with the audience a little bit. “I need your help with one line,” he said. “I keep thinking I should sing, ‘Watching MY hairline recede’ instead of ‘Watching YOUR hairline recede’ …” A woman in the audience let him know, in no uncertain terms: “Sing it the way it’s written.” So he launched into “Just Like This Train,” one of Joni’s greatest songs — she often opens her show with it. But he was also reading the lyrics and he didn’t even seem to know the tune, so it was horrible. I thought, Eric, come ON! You had a little fling with Joni (remember, she sang backup memorably on “Is It Really Love at All,” on his “Blue River” album?), this is a one-time-only special event, couldn’t you have REHEARSED?

To clear away that bad taste, skinny long-legged Joe Jackson ambled over to the piano — “Lookin’ sharp!” someone called out — to accompany Joy Askew on “Down to You.” (I’ve decided “Down to You,” a dense and devastating depiction of a one-night stand, is one of the three greatest pop songs ever written, behind the Gershwins’ “Someone to Watch Over Me” and Leonard Cohen’s “Famous Blue Raincoat”). Joy is multitalented — I first saw her playing keyboards in Laurie Anderson’s band — and she did some of the vocal arrangements for “Joni’s Jazz.” Her version of “Down to You” was superb. In place of the orchestral midsection, they interpolated a couple of verses of “A Case of You,” and Joe Jackson took a long lovely solo that pulled in a bit of “Unchained Melody” (which Joni references in her song “Chinese Cafe”).

Considering that this show was devoted to the jazz side of Joni Mitchell, I expected to hear a lot stuff from “Mingus,” her collaboration with the great jazz bassist and composer Charles Mingus — “Sweet Sucker Dance” maybe (sung by Jane Siberry?) or “The Dry Cleaner from Des Moines.” But the only thing we heard, aside from the “I’s a Mugging” rap, was “God Must Be a Boogie Man,” sung by Erin Hamilton. She was the discovery of the night for me. I’d never heard of her. It turns out she’s Carol Burnett’s daughter, a big tall angular gal with tattoos all over both arms and her torso, and with a fabulous jazz voice — clear, musical, swinging. The audience, of course, sang along whenever the title came up.

Duncan Sheik was extremely nervous — “The word ‘unworthy’ comes to mind,” he confessed to the audience — but he did a very interesting version of “Court and Spark.” His voice isn’t especially beautiful; it’s kind of earnest and awkward and not particularly musical. But his reading of the lyrics was intelligent and dramatic in a nicely understated way. One of the most intriguing things about this concert, by the way, was hearing men sing Joni Mitchell songs without changing the pronouns. Bravo to singers like Duncan Sheik, willing to enter queer emotional terrain. In Los Angeles several years ago, David Schweizer staged an evening of Joni Mitchell songs, also with black and white, male and female singers. One of the high points of that show was Hinton Battle doing “Court and Spark” — I remember him uncovering a lifetime of romantic illusions in the line “You could complete me and I could complete you….”

Chaka Khan came back to do “The Hissing of Summer Lawns” and gave out a fascinating bit of secret Joni lore: that the song was inspired by a visit to Jose Feliciano’s house! She was going on and on about that and checked in with Joni to confirm the story, and Joni had her finger to her lips going Shhhhhh! As in, “You weren’t supposed to repeat that story, knucklehead!” Kinda blows your mind, though, doesn’t it? Anyway, again Chaka blew the melody wide open. She had a great rapport with Vernon Reid and the band — they let her blow, and just when you thought she was going to go into one of her Chaka screams and never stop, she would come right in on the beat. My respect for her musicianship tripled seeing her perform live. Wonder what she’s like when she’s on tour with Prince (‘scuse me, The Artist).

Chaka had the audience eating out of her hand and she was ready to make herself at home and play another song or two, but when she looked over at the producer to get an OK for that, they were frantically making cutthroat gestures, so she sort of wilted and dragged her heels offstage with her diva-tail between her legs. One of the backup singers, Sheryl Marshall, was next up to sing lead, and she looked a little nervous, especially with the crowd calling out for more Chaka. Luckily, she was amazing, barreling through a high-speed, hard-rocking ska version of “Raised on Robbery.”

The first half ended with John Kelly’s intense version of “Shadows and Light,” almost a capella, with the three backup singers standing in for The Persuasions (who sing with Joni on the live-album version). Not too many people outside of New York know who John Kelly is, but he’s an extraordinary performance artist/dancer/actor/singer with a countertenor voice, so he sings Joni’s songs in their original keys. His impersonation of Joni is quite serious, a little bit satirical, often hilarious and always loving. Tonight he wasn’t doing the wig thing but came out as a boy with a dyed-blond Mohawk, camouflage T-shirt and black jeans. He does “Shadows and Light” with an almost Biblical fervor. Again, Joni leapt to her feet applauding at the end.

At intermission, while Stephen and I were nibbling our way through beet salad and tuna fish sandwiches and Fresh Samantha, I heard my name and turned around to find my friend Henry Connell, an art director at Conde Nast. Of all the Joni queens I know, Henry is the biggest of them all. (I’m convinced that Joni Mitchell is to my generation of gay men what Judy Garland was to our elders.) Shockingly, Henry hadn’t heard about the concert until 9:00 this evening when he picked up a voicemail message that cryptically referred to “seeing you later in Central Park.” Once he found out what was going on, he made a beeline over and wound up sneaking into the press section and sitting next to Claire, whom he works with at Glamour. Of course, he was beside himself to be sitting directly behind Joni, two rows away, scrutinizing her every move — her every puff of cigarette, her every swig of Coke. But he’s met Joni before. He wheedled his way into her birthday party at Fez a couple of years ago (that famous occasion where a drunken Chryssie Hynde made a fool of herself professing her love for Joni, to the point of attempting to strangle Carly Simon when Carly tried to shush her) and got to shyly shake paws with her in the dressing room afterwards.

The idea of hearing the entire “Hejira” album performed live by different singers was more exciting in anticipation than in execution. It’s such a perfect album, in its eccentric logorrheic Pat Metheny-Jaco Pastorius kind of way, that it’s hard to know how anyone could match it, let alone surpass it, and the singers who approached the songs respectfully mostly fell flat — Joy Askew’s “Coyote,” John Kelly’s “Amelia,” Prince Be’s “Song for Sharon.” Eric Anderson was again really awful stumbling his way through “Furry Sings the Blues.” The most interesting moment of his performance was when his lyric sheet blew away. While a stagehand chased it around the stage, Eric signalled the band to take over, and boy, did they. I haven’t said enough about this fantastic band. Jerome Harris played delicate, angelic acoustic guitar on the songs that didn’t require Vernon Reid’s crunchy rock ‘n’ roll. The wind players were their own section of elegant diva voices — Graham Haynes on cornet, Don Byron on clarinet, Ravi Coltrane as I mentioned (son of The Man, in case you hadn’t guessed), and white-guy Doug Weiselman on flute/sax/guitar/etc. And Brian Charette, who contributed a lot of arrangements and transcriptions, did all kinds of wizardly things on keyboards, nothing showy, always spare and in excellent taste.

Jane Siberry redeemed herself when she came out to sing “A Strange Boy.” (Perfect casting of a strange girl.) Jane talked about how much she loves a particular line from “Amelia” — “Oh Amelia, it was just a false alarm” — especially the dying fall on “alarm,” which she duplicated perfectly. She apologized for holding a lyric sheet and said she’d asked the band to take the tempo really, really slowly so she could get all the words out. She made it a piece of storytelling that I’d never heard quite so clearly, about this wacky skateboarder who still lives with his family. Even military service “couldn’t bring him to maturity/He keeps referring back to school days.” When Jane sang the line about how love is “the strongest poison and medicine of all,” I watched Joni herself shudder at the power and dreadful truth of that line. And Jane slowed down to the point of stopping when she came to a line she declared only Joni Mitchell could have written, about “the stiff-blue-haired- house-rules.”

Chaka Khan returned to sing “Hejira,” and once more turned a Joni Mitchell song inside out. No more a jittery, sensitive internal monologue about being “porous with travel fever” — you couldn’t even understand the way Chaka pronounced that line — the song became a wide-open jazz blowout about freedom, the band churning the rhythm harder than the original album ever does and Chaka flying away from it and back as mysteriously and unerringly as a bird to a telephone wire. She didn’t quite know how to end the song, so she brought out her granddaughter, and the two of them did a little hoochie-coochie hand-dance to bring it home.

Toshi Reagon worked a similar alchemy with “Black Crow,” a song that really lends itself to jazz riffing. Toshi stayed pretty close to Joni’s version until she came to the line about “diving, diving, diving, diving,” which she decided to repeat, stuttering the second time around, and inspiring the band to unleash in a fury of swooping funk riffing. Toshi waved Chaka onstage, and the two of them went into an extended call-and-response on the chorus. But instead of battle-of-the-divas for high notes or held notes or sheer lung power, they went the other direction altogether and took it down to a quiet intertwining dance that you could see repeatedly amazing and delighting Vernon Reid, who let them go as far as they wanted to go. Toshi Reagon put a down payment on some legendary-singer status tonight.

Erin Hamilton’s cool, clear, hipster-June-Christy voice perfectly suited “Blue Hotel Room.” (How come more cabaret-type singers don’t do this song, or “Sweet Sucker Dance” for that matter?) Stephen and I shared a chuckle about our favorite line, the one about the pretty girls “hanging on your boom-boom pachyderm.” I know “Refuge of the Roads” is Henry’s very favorite Joni Mitchell song, which I don’t understand — I find it overlong and kind of boring, and Duncan Sheik’s performance didn’t convince me otherwise. But he was sweet and humble about it. He came out and said, “I’m going to need some friends of the spirit on this one.” He’s not great at holding notes and asked the audience to sing along when the title line came up. As so often happens with Joni Mitchell, you can hear these songs over and over again and suddenly catch a line that has never really registered before. For me, the biggest example of that was this extraordinary verse from “Refuge of the Roads,” which maybe Duncan Sheik’s famous Buddhism highlighted for me:

In a highway service station

Over the month of June

Was a photograph of the earth

Taken coming back from the moon

And you couldn’t see a city

On that marbled bowling ball

Or a forest or a highway

Or me here least of all……

And suddenly it was over, except for the encore. Jon Hendricks and Annie Ross came out, not-so-surprisingly, and sang “Twisted,” which Annie wrote. She looked great, with dyed-red hair, rattling through the song the way she’s done for almost 40 years. Since Hendricks had nothing to but say “What?” every now and then, they segued into “Jumpin’ at the Woodside” (Joni be damned). Then the producer brought Joni herself out. She bowed and accepted flowers and seemed completely delighted to bask in the attention. Ever-unpredictable — the first thing she said was “Chaka did my hair, how do you like it?” The stage filled up with the whole band and all the singers, and they launched into “Help Me,” expecting Joni to take the lead. But she wasn’t prepared to sing. “I’m on vacation!” she protested, so Chaka and the other singers sort of filled in. John Kelly looked especially radiant and happy to be standing onstage with Joni singing “We love our lovin’/But not like we love our freedom!”

The publicist for Central Park Summerstage had come around and slipped Stephen a couple of passes to the reception afterwards. He didn’t want to go. “Joni hates me,” he whimpered. But I convinced him that it would be fun to say hi to Duncan Sheik and Jane Siberry and John Kelly, all of whom he’s written very nicely about, and he finally relented. As it turned out, most of the artists hung out backstage, where Joni was obviously holding court, and stayed away from the reception, a spread of wine and desserts laid out in the pergola alongside the Rumsey Playfield. So we stood near the entrance and chatted with Jim Farber and Claire, scoring the concert from top to bottom. Jim is another hard-core Joni-hound. He said he owns 7 copies of “Hejira,” in every format (except 8-track, he admitted on closer questioning). Eventually, a few of the artists straggled in. Chaka came in clutching the hand of her boyfriend, a big black man in a white suit. “You were fabulous!” I blurted out when she passed, and she responded with surprising shyness. John Kelly came in holding hands with his boyfriend, and later we went and chatted with them. John and Stephen had never met. People are always pleased and slightly intimidated to meet Stephen. Since they read his reviews in the Times every day, they feel like they know him, and yet here he is in the flesh. John asked him what “Hissing of Summer Lawns” sounded like when it first came out, and they talked about how revolutionary it was. John was leaving the next day to spend the summer in Provincetown performing “Paved Paradise.”

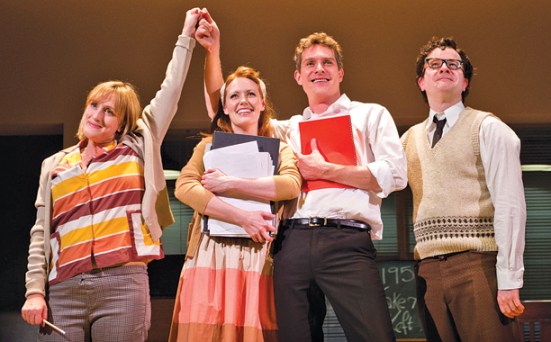

As we were leaving the reception, I saw Jane Siberry walking toward us with a male friend of hers, and I couldn’t resist stopping her and introducing myself and Stephen. She heard our names and looked at us curiously and said, “Why do I know those names?” I said, “We’ve both written a lot about you for years, Stephen in the New York Times, me in Rolling Stone and the Village Voice.” Finally, it clicked. “Stephen! I’ve used your quote about ‘When I was a boy’ for years!” They chatted about the difficulties Jane has had starting her own record label while I talked her friend into snapping a picture of the three of us together. “You should be on Nonesuch Records,” Stephen suggested. She gave him an are-you-crazy look. She wants to do it herself. “You’re very brave,” he said. “I would be brave if it were hard,” she said coolly, “but it’s not hard.” She gave us each her new calling card, which says “Sheeba — ARTIST OWNED” and has a little picture of a Wild West woman in a long skirt pointing a rifle into the distance. As we were talking, our voices were increasingly drowned out by a motor droning nearby. Jane looked over her shoulder and said, “They’re mowing the Astroturf.”

Relieved to have avoided any confrontation with Joni, Stephen headed west toward Tavern on the Green and home. I walked south, swinging my picnic basket and thinking: This is one of those nights that makes it worth it to live in New York.