April 16 – OK, American Idiot. Spectacular staging by Michael Mayer, who masterminded Spring Awakening, my favorite musical of the last 10 years and one of the most exciting and influential Broadway shows in recent memory. Mayer has his usual weaponry with him: dazzling set by Christine Jones, an art installation I’d be happy to visit on its own, pocked with 37 TV sets creating a Big Brother rec room from hell; state-of-the-art theatrical rock-concert lighting by Kevin Adams; smart original choreography by Steven Hoggett (who organized the memorable movement stuff in Black Watch); real rock ‘n’ roll played by an onstage band (with arrangements by Tom Kitt of Next to Normal fame); fantastically energetic performances by a young cast of all different sizes and shapes.

That much was exciting to me for about half the show. But ultimately the Green Day songs just didn’t hold up as theatrical storytelling for me. I don’t know the album, so the words weren’t familiar to me, and they don’t really read from the stage. The songs are peppy and melodic but eventually they start to run together – there’s one strand of angry white-boy blare and another strand of acoustic emo ballad. Mayer has taken Green Day’s catalogue and shaped a storyline to thread the songs together, focusing on three main characters: John Gallagher’s Johnny aka Jesus of Suburbia, who flees the suburbs for the big city to make it as a musician but has more success as a junkie and a half-hearted lover (his girlfriend, the impressive Rebecca Naomi Jones, is known only as Whatsername); Will, who would have joined that expedition but got his girlfriend pregnant so stays home planted on the sofa watching TV (the sadly underutilized Michael Esper); and Tunny, who (in a witty sequence) gets mesmerized by an Army recruitment video, goes to Iraq, gets his leg blown off, and comes home with a wheelchair and his nurse-wife. (Tunny is played by Stark Sands, for me the finest performance in the show and he gets to do an aerial ballet with his Extraordinary Girl that isn’t exactly like “Can You Feel the Love Tonight” — see below.) Unfortunately, these stories come off as too generic to be really interesting – they’re sort of generational archetypes, like the characters in Twyla Tharp’s Billy Joel show Movin’ Out. Recognizable and forgettable at the same time.

That much was exciting to me for about half the show. But ultimately the Green Day songs just didn’t hold up as theatrical storytelling for me. I don’t know the album, so the words weren’t familiar to me, and they don’t really read from the stage. The songs are peppy and melodic but eventually they start to run together – there’s one strand of angry white-boy blare and another strand of acoustic emo ballad. Mayer has taken Green Day’s catalogue and shaped a storyline to thread the songs together, focusing on three main characters: John Gallagher’s Johnny aka Jesus of Suburbia, who flees the suburbs for the big city to make it as a musician but has more success as a junkie and a half-hearted lover (his girlfriend, the impressive Rebecca Naomi Jones, is known only as Whatsername); Will, who would have joined that expedition but got his girlfriend pregnant so stays home planted on the sofa watching TV (the sadly underutilized Michael Esper); and Tunny, who (in a witty sequence) gets mesmerized by an Army recruitment video, goes to Iraq, gets his leg blown off, and comes home with a wheelchair and his nurse-wife. (Tunny is played by Stark Sands, for me the finest performance in the show and he gets to do an aerial ballet with his Extraordinary Girl that isn’t exactly like “Can You Feel the Love Tonight” — see below.) Unfortunately, these stories come off as too generic to be really interesting – they’re sort of generational archetypes, like the characters in Twyla Tharp’s Billy Joel show Movin’ Out. Recognizable and forgettable at the same time.

I wanted to love this show but couldn’t quite get there. Still, I admire Michael Mayer’s fierce devotion to channeling the defiance, anger, confusion, and hormonal power of youth into an alive theatrical canvas. And I respect the conceptual arc of the show – the title starts off as a reference to George W. Bush and his misguided “redneck agenda” but winds up referring to Johnny himself, who has to face the consequences of his own idiotic actions and consider what else is possible now.

Archive for the 'performance diary' Category

Performance diary: AMERICAN IDIOT

April 21, 2010Performance diary: Marina Abramovic and ANYONE CAN WHISTLE

April 12, 2010April 8 – Marina Abramovic’s retrospective at MOMA, “The Artist Is Present,” includes many of her intense body-based performances recreated by a squadron of young recruits. There’s the one where two naked performers stand in a doorway so that those wishing to pass from one room to another have to brush against them. (Originally this was the only entrance to a gallery show, and the performers were a naked man and a naked woman. Watching the documentary film adjacent to the current installation, you can witness how most people enter without looking at either performer and most of them choose to face the woman rather than the man. The gender aspect was nullified the day I visited MOMA, when both performers were women. Plus, it’s not the only way into the room so anyone can avoid touching naked people.) There’s “Hair Piece,” in which a man and a woman sit back to back, their long hair tied together. My favorite body piece had a naked man lying on his back with a skeleton lying on top of him; in the same room is a series of films projected onto the wall, one of a dozen naked men humping a grassy field, another of women pulling up their skirts and exposing their crotches to the falling rain. I admire Abramovic’s commitment to the body as art, though the work is very very cerebral, not very erotic or even emotionally compelling. She likes durational pieces, and nothing she’s done before has been quite as demanding as her current residency at MOMA, where she sits in the big rotunda on the second floor at a table (below, in red dress) while visitors come and sit opposite her silently for as long as they want. I perceive it as a form of darshan (that’s when spiritual teachers give audience to their devotees one at a time, usually very briefly), an encounter with the artist or guru as a mirror of oneself. Spectators do seem to be taking it that seriously. When I walked by, two different young somber-looking women sat opposite Abramovic, the two of them staring at one another. The guard told me that some people have been sitting with her for hours at a time and if you don’t get in line by 10:30 am you’re not likely to get your chance that day. In addition to the spiritual presence aspect, there’s something very Warholian about this performance as well – it takes place surrounded by fancy lighting, in the atmosphere of media circus.

I was more taken with the performative aspects of the William Kentridge show, “Five Themes.” His animated films are very beautiful and worth taking the time to sit through. I especially admired “Ubu Tells the Truth,” a fascinating take on South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Committee hearings, in which perpetrators of horrendous crimes during the apartheid era were granted amnesty for telling their stories – a theoretically healing process for the country, but paradoxically also a public airing of outrageous brutalities (Ubu-esque is a terrific way of framing them – a reference to Alfred Jarry’s fictional tyrant-clown). There’s also an elaborate hour-long show featuring an adaptation of The Magic Flute on a scale model of an opera stage – something I want to go back and spend more time with another day.

April 11 – Anyone Can Whistle is the kind of show that the Encores! series at City Center was created to present: a flawed musical that flopped in its day, hasn’t been seen much, isn’t really worth a full-scale revival, but has a score that’s worth hearing under circumstances that aren’t too demanding. Most of the time when I go to Encores!, I assume I’m going to see a pretty dumb show with a lame book, but if there are a couple of fine musical numbers and a handful of delightful performances I count myself lucky. Anyone Can Whistle definitely had one of the better casts in my experience: Donna Murphy as Cora Hoover Hooper, the brassy, maniacal mayor of a small-town that needs some kind of miracle — no matter how phony — to survive economically (Angela Lansbury played her originally); Edward Hibbert as Comptroller Schub, her partner in crime; Sutton Foster as Fay Apple, the head nurse at the local psychiatric hospital, sensitively referred to as The Cookie Jar; and Raul Esparza as J. Bowden Hapgood, who arrives in town as a patient and gets mistaken for the doctor-savior whose job is to decide definitively who’s crazy and who’s not.

The premise for Arthur Laurents’ 1964 play (with songs, of course, by Stephen Sondheim) comes straight from the heart of the countercultural ‘60s, when the very notions of sanity and craziness, right and wrong were up for questioning. The play is a kind of fractured fairy tale out of a Nichols-and-May nightclub routine, with the kind of sweetly neurotic mental patients and caricatured crooked authority figures that populated Jean Anouilh’s The Madwoman of Chaillot and the long-running cult film King of Hearts. Simplistic and vaudevillean, and yet Laurents was getting at the arbitrariness of classifying mental illness (after all, he and Sondheim were both gay guys in psychoanalysis at a time when homosexuality was officially designated a mental illness). And the hilarious, crazy way that the townspeople unquestioningly go along with Hapgood’s dividing them up into two factions – the A team and the 1 team, both of whom consider themselves superior – speaks to the fierce us-against-them state of American politics today.

[Further thoughts: Anyone Can Whistle was written right in the midst of the tumultuous civil rights movement, when crazed white racists were bombing black churches and Southern white cops were setting attack dogs on non-violent freedom marchers. And the McCarthy era was fresh in the memory of politically alert New York Jewish artists like Arthur Laurents. Those events are part of the backdrop for songs like “Simple,” which cheerfully trots out a series of syllogism: the opposite of dark is bright, the opposite of bright is dumb, therefore dark = dumb; the opposite of left is right, the opposite of right is wrong, therefore left = wrong. That’s a lot of political content for a musical comedy circa 1964, plus it’s delivered in an edgy, Brechtian way — not by modelling Right Thinking for the audience but by espousing offensive sentiments as if they were acceptable, forcing the audience to actively object rather than sink into the warm bath of agreement. David Gursky, Rob Berman’s assistant musical director for the show, told Andy and me afterwards that Angela Lansbury told the company that at the curtain call for the original production, the actors could totally feel the hatred coming from the audience.]

There’s a lot going on, emotionally and psychologically, amidst the play’s crazy cartoon atmosphere. Certainly, the mayor is a dazzling and entertaining monster, and Donna Murphy had a ball playing some wacky mixture of Jackie Kennedy, Tammy Faye Bakker, Kay Thompson, Ethel Merman, and Barbara Streisand. The always-appealing Sutton Foster got to play both the buttoned-down Nurse Apple and her liberated faux-French alter-ego in red dress and wig. “I love a woman who comes with an accent” was my favorite smutty line, spoken by Raul Esparza, suitably genial and manic as Hapgood. Once considered an obscure Sondheim score, Anyone Can Whistle brims with songs we now call classics: in addition to the title song and “There Won’t Be Trumpets” (which Foster sang with her usual dazzling lucidity), there’s “Everybody Says Don’t” (Esparza) and the ballad I can’t get out of my head, “With So Little to Be Sure Of.”

Performance diary: THE NOSE, Linda Mironti, and BLOODY BLOODY ANDREW JACKSON

March 28, 2010

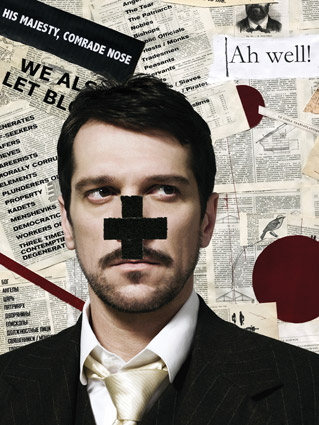

March 25 – I’m exactly the audience for Peter Gelb’s conception of the Metropolitan Opera. Not that I’m so young, but for the 30 years I’ve lived in New York I’ve very rarely attended performances at the Met. I’m a theater guy, and most of the productions there have been stodgy to an extreme. I’m not well-versed in classical music and I don’t follow singers or conductors, so I could care less about comparing this diva to that diva in the umpteenth iteration of the war horses. Most of what I know about opera comes from following the career of Peter Sellars, who favors highly theatrical, high-concept (sometimes gimmicky) stagings of Mozart and Handel operas or brand-new pieces. Since Gelb took over as general manager, I’ve bought tickets to four or five productions, mainly to see the work of directors I admire (Patrice Chereau, Robert Lepage). I wasn’t exactly dying to see Shostakovich’s The Nose – I don’t think anyone is, really – but I got intrigued by the New Yorker profile of William Kentridge, the South African artist whom the Met engaged to design and direct the show, and my friend Stanley made a pilgrimage from San Francisco just to see the Kentridge show at MOMA (which he saw on the last day of its run at SF MOMA) and the opera. So we all went together, Stanley and I and his friends Arunima and Deane.

My first and strongest impression was: wow, at last New York is getting European-style opera productions on a grand scale. Visually, The Nose is a knockout from the moment you walk in the door. Kentridge’s pre-show curtain is a crazy constructivist collage that already makes the room alive with energy, expectation, and historical content (both artistic and political). And the visual invention never stops – now that I think about it, it’s a little like Bill T. Jones’ production of Fela!, a flood of projections, videos, titles, and animations that keeps the visual field alive and interacting with the music and the story at all times (the exact opposite of the traditional park-and-bark style of opera staging). The score is very quirky, dissonant, angular – admirably unconventional but hard for me to love, although it’s exactly what you might imagine a 22-year-old super-talented composer in the thrall of Berg’s Wozzeck. The absurdist story – man has nose, man loses nose, man gets nose back – had all kinds of political and social meanings in Shostakovich’s (and Gogol’s) Russia. A piece of it that resonated with contemporary American life is the public’s mindless fascination with idiotic tabloid news stories (remember the balloon boy?). Paolo Szot’s performance in the central role was certainly a sharp contrast from what his did across the plaza in South Pacific – again, hard to love but admirable. Andrei Popov’s piercing tenor as the Police Inspector was also impressive. But mostly I was dazzled and thrilled by Kentridge’s energetic design, which realizes the artistic ambitions and experiments of Russian constructivist art and theater that Stalin shut down. I especially loved the films of the disembodied nose superimposed on old footage (of Shostakovich at the piano, of ballet dancer Anna Pavlova). Stanley and Nima and Deane had spent a couple of afternoons at MOMA and were excited to talk about the parallels between the opera design and Kentridge’s artwork, among other things, over a delicious dinner at Whym afterwards.

March 26 – Friends and family of Linda Mironti packed out the upstairs room at the Duplex for her show, “La Dolce Vita” (above). Linda and I have been friends for almost ten years – she and Michael Mele run Il Chiostro, whose week-long retreats in Italy include the gay men’s program I co-facilitate, “Come to Your Senses.” Linda’s a wonderful singer, and in this show she tells stories about her Italian grandfather and her years of toiling in Italian recording studios only to find her albums showing up years later on the charts in Korea. She sang a raunchy song about the physical indignities plaguing middle-aged women, which had the audience roaring with laughter. For me, the highlight of the show was the finale, John Lennon’s “Imagine” reconceived as a blues – though when I complimented Linda on it afterwards, she confessed that she stole the idea from Ray Charles. Well, if you’re gonna steal, you might as well steal from the best, eh?

March 27 – I’ve never seen the work of Les Freres Corbusiers before and now, after seeing their new musical Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson at the Public Theater, I’m kicking myself. I wish I’d seen them all, if they were anywhere near as good as BBAJ. Their program bio describes LFC as “a NY-based company devoted to aggressively visceral theatre combining historical revisionism, sophomoric humor and rigorous academic research. The company is committed to the notion of a Populist Theatre that draws on prevailing tastes and comedic sensibilities to speak directly to the mainstream audience routinely ignored by the American Theatre. Les Freres rejects the shy music, seamless dramaturgy and muted performance style of the 20th century in favor of the anarchic, the rude, the juvenile, the spectacle.” How’s that for a manifesto? It’s 100% accurate. The visceral begins when you walk in the door. I’ve been seeing shows at the Newman for 30 years, and I’ve never seen that space so transformed from wall to wall into an intimate nightclub ambience, a la Blue Man Group, with cool enough pre-show music that Andy and I were constantly checking Shazam to see what was playing (Spoon, Tegan and Sara, A.C. Newman). The show is indeed a historical pageant about the former POTUS (a renowned yahoo populist who rode into the White House on a flood of anti-government resentment) delivered in a totally burlesque, history-for-dummies style: hyped-up, anachronistic, slangy, no-joke-too-dumb, ADD to the max, stuffed full of music played by an onstage rock band, some songs lasting 30 seconds, Saturday Night Live meets Spring Awakening on speed. It’s the kind of thing I might usually abhor…and yet it captivated me, entertained me, enlightened me, and made me think. Although it seems to be recycling LCD humor, that’s a kind of pose – its aggressively relentless barrage of cultural references (from Michel Foucault to Valtrex) and edgy joking reminded me less of bad improv comedy than of smart rock bands like Of Montreal. (For example, there are very few characters who aren’t portrayed as big fags at one point or another, from Martin Van Buren and John Quincy Adams to AJ himself. This kind of gay-as-automatic-laugh-line could very easily grate on my nerves but is taken to such extremes here that it’s hilarious.) And I learned a lot about the crazy chaos of early American history. If I ever learned it, I hadn’t remembered that Jackson created the Democratic Party, outraged by the elitism of Republicans (!!). I’d been associating Jackson with George W. Bush but in this president-as-rockstar retelling he uncannily conjures Obama at times. But the piece doesn’t take one point of view or settle for easy parallels. The “serious” content of the piece is in constant contrast to the “silly” style, which I love. I’m totally impressed by Alex Timbers, the writer-director. Michael Friedman’s music rocks, and the performers – from Benjamin Walker as Andrew Jackson on down – give it their all.

Performance diary: NORTH ATLANTIC

March 19, 2010

March 18 – The Wooster Group’s North Atlantic at the Baryshnikov Arts Center. Fantastic show! When the Wooster Group first mounted North Atlantic in 1984, it was an anomaly among their works – an actual complete play, as opposed to the multimedia spectacles they’d previously done that included fragments of classic plays exploded and Woosterized. At the time, it was primarily a genre piece playing off clichés of old war movies funneled through author Jim Strahs’ machine-gun-rapid, energetically obscene, imaginatively free language. Commissioned as a collaboration with a Dutch company (Globe Theater in Eindhoven), it began as a very, very loose adaptation of South Pacific. (And I use the term “loose” purposely as an excuse to quote one of my favorite lines from the play: BENDERS: Now, don’t tease me, Ann. Is she really that way? Is she really that loose? ANN Loose! Why my goodness, General, you could drive a dump-truck down that alley and K-turn without even using the rear-view mirror.) Aboard an aircraft carrier off the coast of Europe, a crew of male navy intelligence officers and female “nurse/word-processors” are engaged in some elaborate activity having to do with coding and decoding military messages…or maybe they’re a decoy operation trying to draw enemy attention away from the real operation. But of course they spend most of their time trying to entertain themselves telling filthy jokes, plotting sexual intrigues, fighting, singing, dancing, and planning a Wet Uniform Contest. The original cast featured the founding Woosters in their glory: Spalding Gray, Kate Valk, Ron Vawter, Willem Dafoe, and Peyton Smith, with Nancy Reilly, Michael Stumm, Anna Kohler and Jeff Webster. It was revived in 1999 with a cast that included Steve Buscemi and new Wooster stars Ari Fliakos and Scott Shepherd.

Now the play takes on a whole other currency, since we’re in the midst of a war where intercepting and interpreting terrorist communications is front and center, not to mention interrogating suspects and sexual politics within the military. But just in case that sounds like some kind of straightforward earnest plot-oriented gritty realistic play, rest assured that it’s still classic Wooster Group: high-powered acting and exquisitely choreographed theatrical chaos. The cast is fantastic: Ari Fliakos as Chizzum, the hot-headed, unbelievably fast-talking captain (originally the Ron Vawter role), Kate Valk as the goofy, sexy Ensign Ann Pusey, Paul Lazar as the creepy General Benders (originally played by Spalding Gray), Scott Shepherd as visiting hot-shot Lud (the Willem Dafoe role), Frances MacDormand as Master Sergeant Mary Bryzynsky (Peyton’s role), and a bunch of terrific young new Wooster-ites, including Steve Cuiffo and Zachary Oberzan who are hilarious and wonderful as two doofy Marines under Chizzum’s command. Typical for the Wooster Group, even though they’ve done the show a couple of times before, it never looks exactly the way it did before – there’s always tweaking and adapting to the space, the actors, and to the visual/theatrical whims of genius director Elizabeth LeCompte. The final tableau is one I didn’t remember – maybe it was always there, but it’s amazing to encounter. And the performed version differs quite a bit from the published version of the play, which you can download from Strahs’ website along with his other plays and his fiction.

This show inaugurates the Wooster Group’s residency at the Baryshnikov Arts Center – a step up from their original home base, the Performing Garage, in terms of capacity and room to maneuver. Weirdly, though the seats look plush, they’re not so comfortable – my butt never falls asleep at the theater but it was uncomfortably numb before the 90-minute intermissionless show was over. Excited crowd in the house, a lot of press. I chatted beforehand with filmmaker Michael Almereyda – good to catch up – and I brought with me a posse of 8, some Wooster Group veterans, and some virgins, including Andy, whose brains were absolutely fried by the show, and Marta, who was super-thrilled to be sitting a few feet away from Frances MacDormand, whom she idolizes. Then when we went to Market Café for dinner afterwards, MacDormand and two friends plunked down at the table next to us, and Marta went into fits of fangirl frenzy. I emboldened myself to chat MacDormand up — she was annoyed by the interruption but patiently indulged me as I showed her pictures on the Harry Kondoleon website of her in a blond wig in the Yale Repetory Theatre production of Harry’s play Rococo, back in 1981.