August 2 – Somehow I managed not to see Marc Wolf’s Obie Award-winning performance Another American: Asking and Telling when he first performed it in 1999-2000 at the New Group, although I heard very favorable things about it. I was under the mistaken impression that Wolf himself had been in the military and was discoursing about his own experience as well as that of others. Only now, when he revived the show for a series of 5 Monday-night performances at the DR2 Theatre in Union Square, do I realize that he did an Anna Deveare Smith number, going on the road and interviewing a wide range of people about the topic of gays serving in the military. He sculpted a play out of his interviews and plays all the various subjects: men and women, gay and straight, military and non-military, pro-DADT and agin. It’s a fantastic show. Wolf is an excellent (and strikingly handsome) actor who is able to transform himself vocally and physically so at times you can’t believe you’re seeing the same guy, even though he uses a minimum of props and costumes. Among the most memorable characters he impersonates are Miriam Ben-Shalom (the first openly gay person to serve in the military, after she spent years fighting an involuntary discharge), the mother of Allen Schindler (a gay Navy man who was beaten to death by shipmates), the guy who invented the expression “don’t ask don’t tell” (a straight academic who doesn’t think gays should be allowed to serve), and a very flamboyant ex-Marine whose fellow soldiers in Vietnam nicknamed him “Mary Alice” and accepted him wholeheartedly (he is repeatedly caught up on the brink of tears remembering the guys who didn’t make it back from that war). The little pocket of information Wolf dramatizes that I hadn’t thought about was the way gay soldiers have been treated by the military in the period between discovery and discharge, which was often brutal and horrifying. The show was beautifully performed and very well directed by Joe Mantello. My friend Wolfie, who knows the actor, corralled Andy and me into going, and we were joined by Stephen Soba and Jonathan Arnold, who sported an amazing pair of trousers (see below) that drew compliments from strangers right and left. We had a delicious dinner afterwards at L’Express on Park Avenue.

Archive for the 'performance diary' Category

Performance diary: ANOTHER AMERICAN: asking and telling

August 7, 2010Performance diary: Abida Parveen and other Sufi musicians at Asia Society

July 25, 2010July 22 – Two days after a free concert of Pakistani Sufi music in Union Square, the same lineup appeared at the Asia Society on a program called “Sufis of the Indus.” Co-produced by a group called Pakistani Peace Builders, these concerts were planned specifically to do some cultural repair work after the thwarted terrorist attack on Times Square in April by a Pakistani-American. I only found that out at the concert – I went specifically to hear the great Abida Parveen, as beloved to her Pakistani followers as Oum Khalsoum is to Egyptians, Mercedes Sosa to Argentinians, or Asha Bhosle to Indians. Parveen is widely acknowledged as a master in the form of Kafis, the sung Sufi poetry in languages such as Sindhi, Seraiki and Punjabi. It’s related to qawwali music, the best-known form of Sufi devotional music from Pakistan (thanks to the late Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan), which is traditionally performed by men. I have a couple of her recordings and thought I’d seen her the first time at the World Sacred Music Festival in Fez, Morocco, in 1997. But when I go back and look at the article I wrote about that festival for the Delta Airlines’ in-flight magazine Sky, there’s nothing about Abida, so I guess I must have seen her after that in New York, in the company of other members of the World Music Institute who’d been on the trip to Morocco. (It was an amazing, life-altering trip. I also published an article about it in RFD, “Morocco Diary.”) The two main producers of the Sufi Music Festival were Rachel Cooper, director of cultural programming at the Asia Society, and Zeyba Rahman, former chairperson of WMI and for several years the North American director of the Fez festival. I met Zeyba on the trip to Morocco, and I met Rachel through her connection to the 1990 Los Angeles Festival, curated by Peter Sellars, where she was instrumental in presenting the Royal Court Gamelan from Yogyakarta, Java (one of the festival highlights for me).

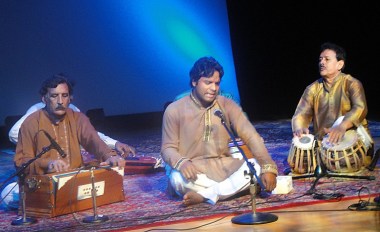

It was a beastly hot night, so I blithely showed up at Asia Society in shorts and Hawaiian shirt only to find the NYC/Pakistani cultural elite dressed to the nines (it was as close as I’ve ever gotten to that nightmare about showing up at school naked). Somehow we ended up sitting in the fourth row center, next to Jay Corcoran and Mike Roberts, for an intermissionless two-and-half-hour extravaganza. It began with many speeches and a lot of thank-yous. The first of five performers was Nadir Abbas, a young protégé of the same teacher who taught Abida Parveen, backed by her main musicians.

The most colorful act of the show was the Soung Fakirs, an all-male company of shrine singers from Sindh connected to the shrine of revered Sufi saint Sachal Sarmast. Their leader was an ancient guy whose long red beard was painted bright red, a color also heavily featured in their dazzling costumes.

The music is a Sufi version of gospel, passionate incantations and ecstatic rhythms praising God and preaching peace, love, and togetherness.

They were followed by rabid virtuoso Haji Sultan Chanay, whose pieces were quieter and more lyrical. He brought on two young women, Zeb and Haniya, a singer and her guitar player, and then Akhtar Chanal Zehri, who cut an exotic figure in his black beard, stark white costume, and a fierce vocal attack that inspires comparisons to rappers.

In between performers, Hameed Haroon made sweetly earnest attempts to provide context for the different artists and how they represent the four different provinces of Pakistan. He also made sure to mention all the accompanying musicians in the show by name, because they weren’t listed in the program. But it was kind of hilarious – he kept saying “of course we all know X-and-such,” spelling out historical and cultural details that were probably completely obvious to the Pakistanis in the audiences, but there was so much information that it was impossible for the rest of us to digest it (well, for me, anyway).

It didn’t matter. We were all there to hear Abida Parveen, and she didn’t disappoint. She sat cross-legged at center stage, big-bodied and big-haired, surrounded by pages and pages of what looked like some combination of handwritten scores, set lists, and lyric crib-sheets. And she sang nonstop for an hour. I don’t have the vocabulary to describe this music, except to liken it to Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan – ecstatic devotional music that starts slow and prayerful, works through a small amount of lyrical content, and then builds through repetition and tight collaboration with her musicians, especially the tabla and harmonium, her left- and right-hand men, both virtuosic and riveting themselves. (YouTube has a bunch of clips, like this one.) I couldn’t take my eyes off the harmonium player’s mesmerizing, masklike face.

Andy had never heard anything like it and afterwards said his head kept exploding as he tried to make sense of how the music was structured, what she was singing about, how the musicians were interacting. Not clear to me, either — I just drank it in. At times she’d say something soft and sweet and the audience would audibly swoon – and inevitably the audience would get caught up clapping along when the faster rhythms kicked into high gear. Party in the temple, y’all.

Performance diary: Lincoln Center Festival productions of A DISAPPEARING NUMBER and TEOREMA

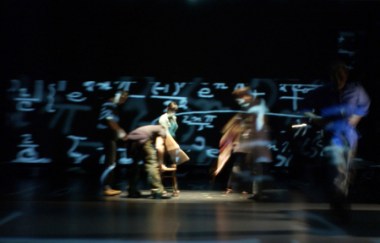

July 20, 2010July 16 – A Disappearing Number, Simon McBurney’s 2007 play with his company Complicite at the Lincoln Center Festival, is a dense and heady piece about mathematics, based on G. H. Hardy’s memoir A Mathematician’s Apology (which McBurney learned about from Michael Ondaatje). It centers on Hardy’s relationship with Srinivasa Ramanujan, a young unschooled Indian math genius who developed some fantastic and very advanced proofs. (The main one demonstrated is called the Riemann zeta function, which proves that 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 … = -1/12.) This historical narrative plays off a parallel fictional story of a British female mathematician and her relationship with an Indian-American hedge fund manager. It’s very theatrical in typical Complicite style. It opens with a wonderful scene of Ruth (Saskia Reeves) giving a lecture on numerical sequences, and then Paul Bhattacharjee (playing the character of Aninda Rao, a colleage of Ruth’s) demonstrating all the ways we’re looking at an artificial environment – sliding walls, doorway to nowhere, revolving screen – actors playing parts – which of course only heightens our ability to be transported through the parallel stories of Hardy and Ramanujan (who died of TB at age 33) and Ruth and Al, with video and shadow plays, and music by Nitin Sawhney, both pre-recorded and played live on tabla. Of course, the music and the couple of dance sections operate on additive principles separate from but related to the mathematics. Equations fill the screen and the stage, much talk of infinity, diverging and converging sequences, the stories traveling back and forth in time, passages repeated for poetic purposes. The refrain that caught me: “A mathematician, like a painter or a poet, is a maker of patterns. And beauty is the first test.”

Andy was completely mesmerized and rendered ecstatic by the sheer math-geekiness of the play. I was tracking all the Robert Lepage-like transformations of the stage and searching for the emotional underpinnings of the biographical narrative and the philosophical argument. And it all came together in the final image for me. McBurney sets up symmetry as a key feature – in nature, in math (infinite possibilities on either side of the equation, positive and negative, and between any two numbers), and in art. Early on Ramanujan is scribbling his wild intuitive proofs on a handheld blackboard out of which suddenly pours a stream of sand, or salt, that piles around his feet. It brought to my mind Tibetan sand mandalas and suggested another iteration of the show’s theme of the interconnectedness of all things, the Upanishads and Walt Whitman, stars and snowflakes as infinite as numbers. And at the end, Ruth has died of a brain aneurysm on a train on her way to a conference in Madras, a few years after miscarrying her child with Al. Al, who’s brought her suitcase of books to toss into the Cauvery, “the Ganges of the South,” where Indians throw the ashes of the dead. Ruth appears, opens her purse, and pours out a stream of sand, salt, ashes. And I got it: infinity is the place where love meets loss. At the curtain call, I was in tears, feeling the eternal infinite of my own losses, and Andy was beaming with joy, as excited as I’ve ever seen him at the theater. He even bought the script in the lobby afterwards.

July 17 – We got on the ferry to Governors Island with Mr. David Zinn and had a very pleasant 20-minute stroll to the remote location where Ivo van Hove’s Toneelgroep Amsterdam performed Teorema, communing briefly with Les Waters (above, modelling DZ-designed tattoos) and Melanie Joseph before going in. I have to laugh, just contemplating the radical juxtaposition of a former military installation hosting a Lincoln Center Festival production of a Dutch adaptation (with English subtitles) of an Italian novel/film by Pasolini. From the minute we walked in, we were clearly in an Ivo van Hove production – the three-walled box set with industrial gray carpeting and modular stylized box furniture bore a family resemblance to van Hove’s productions of Hedda Gabler and The Misanthrope at New York Theater Workshop as well as Opening Night at BAM (all designed by van Hove’s resident designer, partner, and chief collaborator Jan Versweyveld). [I didn’t see van Hove’s production of Cocteau’s Le voix humaine, which must have played in the same location during last year’s New Island Festival.) Playing on a plasma screen at the rear: an episode of Meercat Manor. Soundtrack: a kitschy and then dementedly repetitive loop of the Supremes singing “The Happening.” Hi, Ivo! I love you!

Teorema is Pasolini’s famous 1968 film starring Terence Stamp (above, at the peak of his youthful good looks) as a mysterious handsome stranger who visits an upper middle-class Milanese family and has sex with everyone in the household: maid, mother, son, daughter, father. He brings to all of them a new joy, a liberation Then he leaves, as suddenly as he appears, and each family member is left struggling – and mostly failing — to integrate this liberation into an ongoing life. When I first saw the film, in college in Boston, I thought Teorema was the stranger’s name, and I found the pansexual aspect of the film titillating beyond belief. Seeing it again on DVD recently, in the course of giving myself an ad hoc course on the complete filmography of Pasolini (a great great inspired poetic perverse political filmmaker), I finally understood the film as a kind of schematic essay (teorema = theorem). Yes, in the late sixties, questions about sex and sexuality and their representation in the cinema were very much in the air and constituted the basis for a kind of political dialogue. But as a Marxist, Pasolini was very interested in class-consciousness and how it plays out both in sexual relationships and in artistic representation of history, religion, and erotic life. He also had the guts to shoot his films from an unapologetically gay point of view – just watch how his camera lingers over the crotches of men, the cinema of cruising, in a lusty but not especially pornographic way.

Teorema is Pasolini’s famous 1968 film starring Terence Stamp (above, at the peak of his youthful good looks) as a mysterious handsome stranger who visits an upper middle-class Milanese family and has sex with everyone in the household: maid, mother, son, daughter, father. He brings to all of them a new joy, a liberation Then he leaves, as suddenly as he appears, and each family member is left struggling – and mostly failing — to integrate this liberation into an ongoing life. When I first saw the film, in college in Boston, I thought Teorema was the stranger’s name, and I found the pansexual aspect of the film titillating beyond belief. Seeing it again on DVD recently, in the course of giving myself an ad hoc course on the complete filmography of Pasolini (a great great inspired poetic perverse political filmmaker), I finally understood the film as a kind of schematic essay (teorema = theorem). Yes, in the late sixties, questions about sex and sexuality and their representation in the cinema were very much in the air and constituted the basis for a kind of political dialogue. But as a Marxist, Pasolini was very interested in class-consciousness and how it plays out both in sexual relationships and in artistic representation of history, religion, and erotic life. He also had the guts to shoot his films from an unapologetically gay point of view – just watch how his camera lingers over the crotches of men, the cinema of cruising, in a lusty but not especially pornographic way.

Van Hove’s adaptation (created in collaboration with Willem Bruls) follows the story very closely, though the text presumably comes from the novel Pasolini wrote after making the film (whose dialogue is quite sparse). It is indeed a parable of enlightenment, a drab and unhappy clan exposed to a spiritually infused erotic force that could be seen as God, could be seen as sacred intimacy, could be seen as political salvation (Communism? Obama’s presidency?). The family is white; the guest (played by Chico Kenzari) is some ethnic cocktail, visually signifying Other. Very different from the movie and yet fittingly, the stage production is almost perfectly Brechtian – cool, beautiful, unhurried. The set exposes everything like a laboratory. There is a score performed by a musical ensemble named Bl!ndman, a quartet (three women and one man) who take their places at the top of the show at turntable/consoles in the four corners of the set, facing away from center and one another, fiddling with knobs to produce a drony electronic underscore to the first scene. Later, the musicians sit in a square facing one another to play some Beethoven and Webern as well as original music by Eric Steichim. The actors speak in guttural Dutch while the English subtitles appear in stark black-and-white on four screens around the space. Knowing the story, I was completely absorbed and fascinated by how the production played out the Guest’s sexual coupling with each family member, how each shook off his or her lethargy in the glow of his unconditional love, and then how each one dealt with the aftermath of enlightenment – the mother tries to reproduce her connection with him and slides into sleazy nymphomania; the daughter goes crazy; the son kills himself; the maid (the proletarian, already disposed toward a religious sense of things) embraces the rapture (see below); and the father struggles hardest with the existential challenge of surrendering his ego and material self.

Van Hove’s adaptation (created in collaboration with Willem Bruls) follows the story very closely, though the text presumably comes from the novel Pasolini wrote after making the film (whose dialogue is quite sparse). It is indeed a parable of enlightenment, a drab and unhappy clan exposed to a spiritually infused erotic force that could be seen as God, could be seen as sacred intimacy, could be seen as political salvation (Communism? Obama’s presidency?). The family is white; the guest (played by Chico Kenzari) is some ethnic cocktail, visually signifying Other. Very different from the movie and yet fittingly, the stage production is almost perfectly Brechtian – cool, beautiful, unhurried. The set exposes everything like a laboratory. There is a score performed by a musical ensemble named Bl!ndman, a quartet (three women and one man) who take their places at the top of the show at turntable/consoles in the four corners of the set, facing away from center and one another, fiddling with knobs to produce a drony electronic underscore to the first scene. Later, the musicians sit in a square facing one another to play some Beethoven and Webern as well as original music by Eric Steichim. The actors speak in guttural Dutch while the English subtitles appear in stark black-and-white on four screens around the space. Knowing the story, I was completely absorbed and fascinated by how the production played out the Guest’s sexual coupling with each family member, how each shook off his or her lethargy in the glow of his unconditional love, and then how each one dealt with the aftermath of enlightenment – the mother tries to reproduce her connection with him and slides into sleazy nymphomania; the daughter goes crazy; the son kills himself; the maid (the proletarian, already disposed toward a religious sense of things) embraces the rapture (see below); and the father struggles hardest with the existential challenge of surrendering his ego and material self.

I was thrilled and ecstatic when it was done. Andy was bored…out…of…his…skull. Hated it. David was somewhere in between. Walking back to the boat, we had a good if awkward conversation about our various responses. I marveled at how Teorema was essentially a variation on the same themes that propelled A Disappearing Number – encountering a beautiful idea, a beautiful theory (as in Angels in America), and then trying to incorporate it into your life, which turns out to be an arduous spiritual task. I loved being present for that investigation. But clearly I’m in the minority on this one.

It was a beautiful night, the hot day cooling down to a peachy sunset, Manhattan putting on a glittering light show as we sailed back across the river and headed to Suenos for yummy Mexican food and margaritas.

Performance diary: A Small Act, The Grand Manner, Laurie Anderson at Le Poisson Rouge

July 15, 2010

July 8 – Andy’s job at the United Nations these days required him to compose talking points for UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon (above) to deliver at a screening of Jennifer Arnold’s documentary A Small Act, so he got invited to the screening at HBO and I tagged along as his plus-one. The film tells one of those classic inspiring stories. Decades ago, a Swedish schoolteacher named Hilde Back, who’d fled Nazi Germany as a child (her parents did not survive), signed up for one of those programs where a small monthly donation subsidizes the education of a specific child in Africa – in this case, Chris Mburu from a small village in Kenya. Mburu went on to the University of Nairobi and Harvard Law School and has worked as a human rights activist ever since. The film tracks his efforts to create a scholarship fund in Hilde Back’s name and the competition among village schoolchildren for the three available slots in a given year. As the title suggests, the essence of the film is to demonstrate how one small commitment has unforeseen resonance in the world. Arnold’s documentary tells that story modestly, with a minimum of generic sentimentality and an honest attention to the ambiguities and contradictions of cross-cultural philanthropy and the challenges of education in developing countries. Arnold, Mburu, camerawoman Jennifer Lee, and producer Jeffrey Soros were on-hand for a Q&A afterwards. And in lieu of goodie bags, HBO distributed $10 Good Cards, which allow you to donate money to your favorite charity via the website Network for Good (which they astutely market with the headline “When the people in your life don’t need more STUFF as a gift….”).

July 9 – I’m mildly interested in the story of Katharine (“Kit”) Cornell, one-time first lady of the American theatre, her gay director-husband Guthrie McClintic, and her lesbian lover Gertrude Macy, but A.R. (Pete) Gurney wouldn’t be my first choice of playwright to deliver that story with the panache, understanding, and dishy detail that would satisfy me. The Grand Manner, at Lincoln Center Theater, is based on the author’s brief meeting of these folks backstage at the Martin Beck Theatre during the run of Antony and Cleopatra, back when he was a teenaged autograph hound preceded by a handwritten note of introduction from his grandmother back in Buffalo. Out of this fleeting anecdote Gurney has fashioned a 90-minute drama whose central character is…Pete, the schoolboy. It is a typically tame Gurney drama. The actors show up and do well. Brenda Wehle gets to play Cornell’s tough protective butch girlfriend who says things to the kid like “I’m her great, good friend – do you know what that means?” Boyd Gaines as McClintic gets to stagger around saying “fuck” a lot (not the way we usually experience Gaines, who’s never been invited into David Mamet’s cherished circle). Kate Burton gets to, well, pretend to be grand while describing herself as “a dumpy middle-aged lesbian.” (Her best performance is actually being interviewed in the fascinating edition of the Lincoln Center Theater Review about her own family’s theatrical dynasty. Pick it up when you walk by the theater. ) Bobby Steggert plays Pete, and he’s charming. But oh, so tame.

July 13 – When I heard that Laurie Anderson would be playing at Le Poisson Rouge, I thought it might be really great to see her in such an intimate club setting. But I forgot how much I hate concerts where you have to stand the whole time (after standing in line for 45 minutes waiting to get in). And the gig stood as a promo party for her new Nonesuch CD Homeland, which is not one of her most compelling outings. The songs are minor, meandering, not especially melodic. And the club environment didn’t seem to open up any new possibilities. In fact, weirdly, Laurie seemed to retreat, barely making eye contact with the audience, reading from the script on her music stand. Perhaps she needs the distance of a stage to connect, or seem to connect. Plus, these days she performs without visuals, and I realize only in retrospect that the visuals always added a poetic element that made her songs so much more than the sum of the words and the music. So it was a somewhat disappointing evening. But I suppose it’s the disappointment of a longtime fan whose mind has been blown many times by her wit and invention – how many artists can keep that up for three decades? She had a fascinating band that consisted of a keyboardist, a handsome sax player, three nerdy-boy backup singers (all dressed like Laurie in white shirts and skinny black ties), and one of my culture heroes, the legendary producer Bill Laswell, on bass (a sweaty night in Manhattan, and this stocky hipster was wearing a suit jacket and wool cap – whew). There were a few appearances of Fenway Bergamot, the name Laurie has given to the male character she creates by running her voice through a filter that drops the pitch an octave. And her encores were fascinating, weird, beautiful bursts of solo violin improve. The best songs in concert, as on the new album, were the up-tempo “Only an Expert” (see Laurie’s website for the results of a competition for best remix) and the mournful “Dark Time in the Revolution.” The latter, with its refrain of “they keep calling ’em, calling ‘em up,” seems to belabor the obvious point that wars are fought by kids – but it’s hard to argue with the truth of it, and the refrain gets more emotionally affecting as it goes along, and as the wars drag on.