Here’s what is foremost on my mind politically these days: yes, I am disappointed with President Obama on any number of fronts, but I’m not willing to let that disappointment turn the 2010 midterm election into a referendum on his presidency by thumbing my nose at him. To do so would be to allow the newly energized far-right to gain more power than would be good for anybody.

I suppose I’m one of those who would like to think that Tea Party candidates like Sharron Angle and Christine O’Donnell and Linda McMahon are wingnuts whom the populace can’t possibly consider worthy of office. I am persuaded by David Barsamian’s interview with Chip

Berlet, a journalist who has taken as his subject the rise of right-wing populism, that this would be stupid and naive. The Tea Party, Berlet says, “started out as a fake grass-roots movement funded by political elites. We call them ‘Astro-Turf’ movements. Republican and conveservative poltiical operatives were trying to create the impression that there was a groundswell of antagonism toward the Obama agenda. Some of the early activities were very thinly disguised Astro-Turf, but as the media began to pick up on it — especially Fox News — the Tea Party turned into an actual social movement. It escaped the specific economic-libertarian agenda set for it by Dick Armey, the former Republican House leader from Texas whose organization funds a lot of Tea Party events. Other agendas were brought in: anti-immigrant, anti-gay, anti-abortion, even conspiracy theories about the ‘new world order’ and the UN coming in black helicopters…”

Berlet goes on to say, “Sociologist Rory McVeigh did a great study showing how right-wing movements arise in defense of power and privilege. People on the right are fighting to keep something they don’t want to lose. That’s a strong motivator…You don’t build a campaign of prejudice out of thin air. It has to be rooted in the culture. So you start out with a rhetoric of us versus them: We’re good; they’re bad. We’re going to save America; they’re going to destroy it…It’s portraying the political opposition not as people with whom you disagree but as a force of evil with whom there can be no compromise. How can you compromise with Satan? How can you compromise with the people who want to destroy America? What happens in this situation is that people started getting killed.”

The interview ends with Berlet saying, “When you build a major social movement around scapegoating and resentment, things can move quickly in a bad direction…We’re not going to have a Hitler; we’re not going to have storm troopers marching in the streets. What we’re going to have is a Republican Party that moves to the Right and openly embraces racist, xenophobic ideologies, following the anger of the predominantly white Republic middle class. And the Democrats will follow them, or at least not mount a real opposition. There will be more anti-Muslim and antifeminist and antigay rhetoric. There will be more support for foreign intervention. And that’s our future, unless the progressive movement stands up and starts raising hell.”

Meanwhile, in the New Yorker this week there’s a long insightful profile by Nicholas Lehmann of Nevada Senator Harry Reid, the Senate Majority Leader who is one of the main targets that the Tea Party movement (i.e., all the money the Republican party and the oligarchy can come up with) is trying to take down. Reid is anything but a hell-raiser, quite uncharismatic and therefore quite susceptible to media-enflamed attacks by his opponent Sharron Angle. As the New Yorker so often does, Lehmann’s reporting takes us behind the scenes to see exactly how Reid has succeeded as majority leader in helping Obama make any number of legislative gains on the kind of unsexy but overwhelmingly important issues that government is supposed to address but that get undervalued in our crazy media world.

“Obama, with his big congressional majority and keen sense of the fleeting nature of political momentum, decided to be bold in his first two years in office. Although liberal voters are disappointed, the plain truth is that Obama, aided by Nancy Pelosi and Harry Reid, passed much more liberal legislation at the outset of his term than his immediate Democratic predecessors, Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter…In the partnership between the Obama White House and the Reid Senate, Obama supplied the eloquence and grace and originated the policy ideas. Reid’s role was to get it done. Between Obama’s Inauguration, in January, 2009, and the congressional recess early last month, more consequential liberal legislation passed than at any time since the Great Society: health-care reform, the economic-stimulus package, financial regulation, a big education bill, the rescue of the auto industry, and the second phase of the rescue of the big banks. Others (a large expansion of protected public lands, funding for universal broadband access) didn’t get the attention they normally would have.”

And I was very impressed and grateful to read the story in New York magazine by Jesse Green on Tony Kushner, whose analysis of this political moment I share:

“And the LGBT community, what are they, we, looking for? Yes, we’ve been asked to wait a very long time, asked to eat oceans of shit by the Democratic Party; we’ve been 75 percent loyal for decades without a wobble and without a whole lot of help from these people. And it’s important that somebody keeps screaming; the trick is how do you scream, and who do you scream to? If we’re dissatisfied with these Democrats, let’s get better ones instead of fantasies about mass uprisings that are going to resemble the October Revolution. Yes, it might sometimes feel good to throw the newspaper across the room. There’s much criticism of Obama that’s legitimate. He backs down on things, he waffles, like on the mosque, and you wince. And I consider his decision to appeal the Federal court ruling abolishing DADT to be unethical, tremendously destructive, and potentially politically catastrophic. But is Obama really supposed to say, as the first African-American president, that same-sex marriage is his first priority? Clearly he believes in it; he’s a constitutional scholar. It’s not conceivable to me that he believes that state-sponsored marriage should be unavailable to same-sex couples, even if he has religious scruples. But do I think he should have lost the election for the chance to say he supported same-sex marriage? No. Given that we would have had John McCain and Sarah Palin, I would have said, ‘Say anything you need to.’ So if he’s moving very cautiously, with two wars he’s inherited and a collapsing global economy and the planet coming unglued—Okay!”

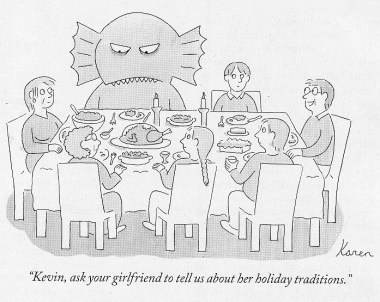

I continue, in my obsessive way, to appreciate and digest the Broadway show Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson for the way it cannily captures the proud, delusional self-righteousness of under-informed ideologues — Jon Meacham, whose biography of Jackson won the Pulitzer Prize last year, writes a detailed (and approving) response to the play in today’s New York Times, “Rocking the Vote, in the 1820s and Now.”