Two interesting long pieces — a profile by Evan Osnos of the young Chinese pop novelist (and race car driver!) Han Han, and a reporting piece by Nick Paumgarten about online dating services, specifically covering OK Cupid, Match.com, and eHarmony. The most remarkable fact in Paumgarten’s story is that he has only been on two dates in his entire life — he’s been married for 23 years to the second woman he dated. Also commendable: Lauren Collins’ “Letter from Luton,” about the English Defense League, a product of the anti-Muslim-immigration sentiment in the U.K. The racism of the EDL lads is very disturbing, but so is a sheik’s refusal to shake a female reporter’s hand.

Archive for the 'In this week's New Yorker' Category

In this week’s New Yorker

June 29, 2011In this week’s New Yorker

June 20, 2011I had the luxury today of sitting on my veranda for several hours this afternoon reading the entire issue of the New Yorker the day it arrived in the mail. Unprecedented! A slightly guilty pleasure but a reward to myself after a period of many days hard work without a break.

Some good stuff I might have skipped on a busier weekday: Rebecca Mead’s profile of Alice Walton, the Wal-Mart heiress who’s building an American art museum in Bentonville, Arkansas; Joan Acocella’s profile of American Ballet Theater’s new artistic director, the Russian emigre Alexei Ratmansky, whose work I now feel compelled to check out; and Adam Gopnik’s personal essay about taking drawing lessons, a humbling experience for a seasoned art critic.

And then there’s Alice Munro’s short story, “Gravel,” as deft and light-handed and remarkable as any Munro story (with the ultra-casual introduction of the central character’s lesbianism a typical Munro touch). I would love to know which editor matches up the New Yorker’s fiction with the photographs that illustrate them — it’s almost always a mysterious and perfect selection.

And Margaret Talbot’s commentary in Talk of the Town, in contrast to most of the media whirl, speaks sensibly about l’affaire Anthony Weiner: “If you were Anthony Weiner’s wife, you’d have your own concerns. But if you were his constituent, and thought he was doing a good job representing you, maybe you’d just as soon ignore his Internet amusements. That’s different from saying that what a politician does in private is never our business. It’s more a tacit acceptance that some of the qualities that launch people into public office—self-regard bordering on narcissism, risk-taking—can also launch them into risks of a more personal kind, and that this doesn’t inevitably reflect on their ability to govern. Maybe it’s an acknowledgment that sometimes there are more important things to talk about. “

In this week’s New Yorker

June 18, 2011another eye opens has been on hiatus for a few weeks, while I’ve been in Germany teaching a workshop. But I’m back and blogging with a vengeance!

The Summer Fiction issue of the New Yorker features a cover by David Hockney (above), drawn/painted on his iPad, and another good sad story by George Saunders called “Home.” But the most remarkable thing in the magazine is Aleksandar Hemon’s Personal History essay, “The Aquarium,” reporting in Joan Didion-like detail about his nine-month-old daughter Isabel’s excruciating and successful battle with brain cancer. If this emotionally upsetting narrative is the A story, there is a fascinating B story having to do with Hemon’s three-year-old daughter’s response to the situation:

The Summer Fiction issue of the New Yorker features a cover by David Hockney (above), drawn/painted on his iPad, and another good sad story by George Saunders called “Home.” But the most remarkable thing in the magazine is Aleksandar Hemon’s Personal History essay, “The Aquarium,” reporting in Joan Didion-like detail about his nine-month-old daughter Isabel’s excruciating and successful battle with brain cancer. If this emotionally upsetting narrative is the A story, there is a fascinating B story having to do with Hemon’s three-year-old daughter’s response to the situation:

“It was sometime in the first few weeks of the ordeal [of her nine-month-old sister’s treatment for a brain tumor] that [three-year-old] Ella began talking about her imaginary brother. Suddenly, in the onslaught of her words, we would discern stories about a brother, who was sometimes a year old, sometimes in high school, and occasionally traveled, for some obscure reason, to Seattle or California, only to return to Chicago to be featured in yet another adventurous monologue of Ella’s.

It is not unusual, of course, for children of Ella’s age to have imaginary friends or siblings. The creation of an imaginary character is related, I believe, to the explosion of linguistic abilities that occurs between the ages of two and four, and rapidly creates an excess of language, which the child may not have enough experience to match. She has to construct imaginary narratives in order to try out the words that she suddenly possesses. Ella now knew the word “California,” for instance, but she had no experience that was in any way related to it; nor could she conceptualize it in its abstract aspect – in its California-ness. Hence, her imaginary brother had to be deployed to the sunny state, which allowed Ella to talk at length as if she knew California. The words demanded the story.

At the same time, the surge in language at this age creates a distinction between exteriority and interiority; the child’s interiority is now expressible and thus possible to externalize; the world doubles. Ella could now talk about what was here and about what was elsewhere; language had made here and elsewhere continuous and simultaneous. Once, during dinner, I asked Ella what her brother was doing at that very moment. He was in her room, she said matter-of-factly, throwing a tantrum.

At first, her brother had no name. When asked what he was called, Ella responded “Googoo Gaga,” which was the nonsensical sound that Malcolm, her five-year-old favorite cousin, made when he didn’t know the word for something. Since Charlie Mingus is practically a deity in our household, we suggested the name Mingus to Ella, and Mingus her brother became. Soon after that, Malcolm gave Ella an inflatable doll of a space alien, which she subsequently elected to embody the existentially slippery Mingus. Though Ella often played with her blown-up brother, the alien’s physical presence was not always required for her to issue pseudoparental orders to Mingus or to tell a story of his escapades. While our world was being reduced to the claustrophobic size of ceaseless dread, Ella’s was expanding.”

In this week’s New Yorker

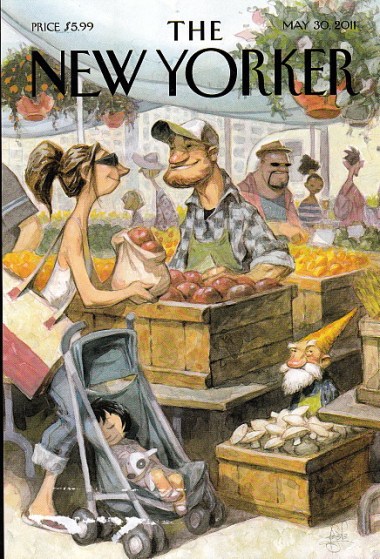

May 28, 2011Yes, it’s farmer’s market season again — yay! And hooray for the clever New Yorker cover with that reminder.

Two excellent pieces in the magazine this week: John Colapinto’s “Strange Fruit,” telling you everything you want to know about the harvesting of acai and the marketing of its (possibly overhyped) medicinal properties; and Rachel Aviv’s “God Knows Where I Am,” the sad tale of a patient who refuses to accept a diagnosis of mental illness and how that plays out in her life. Key quote from the latter: “Today, there are three times as many mentally ill people in jails as in hospitals.”

I was mildly interested in Andrea K. Scott’s profile of Cory Arcangel, whose show at the Whitney I’m mildly interested in seeing. John Lahr is one of those theater critics who so falls in love with artists that he profiles for the New Yorker that I find his always-glowing opinions of their subsequent work to be suspect — cf. his review of Sarah Ruhl’s Stage Kiss in Chicago. But I’ve yet to be grabbed by any of Ruhl’s work. If I had time to read Adam Kirsch’s piece on Rabindranath Tagore, I’ll bet I’d glean stuff that would interest me. And I hope to get around to reading Kate Walbert’s short story “M&M World.”

In this week’s New Yorker

May 22, 2011Several long absorbing articles in this week’s New Yorker:

— Jill Lepore reviews two biographies of Clarence Darrow, in the process delivering a capsule biography of the most famous lawyer in American history and his principled defense of labor unions and organizers. In 1903, representing the United Mine Workers in Pennsylvania, he wrote, “Five hundred dollars a year is a big price for taking your life and your limbs in your hand and going down into the earth to dig up coal to make somebody else rich.”

— Jane Mayer writes a detailed and complicated story about whistle-blowersinside the federal government, focusing on the case of Thomas Drake, a former senior executive at the National Security Agency who faces serious jail time for sharing unclassified documents with Congressional investigators about grotesque waste and mismanagement in his agency’s development of surveillance technology. “Even in an age in which computerized feats are commonplace, the N.S.A.’s capabilities are breathtaking. The agency reportedly has the capacity to intercept and download, every six hours, electronic communications equivalent to the contents of the Library of Congress. Three times the size of the C.I.A., and with a third of the U.S.’s entire intelligence budget, the N.S.A. has a five-thousand-acre campus at Fort Meade protected by iris scanners and facial-recognition devices. The electric bill there is said to surpass seventy million dollars a year.” A major point of the story is that the Obama administration has been just as severe in punishing whistle-blowers as the previous administration.

— Kelefa Sanneh’s “Where’s Earl?” is one of those stories that astonish me when they turn up in the New Yorker. It’s an introduction to a pop music phenomenon that I haven’t heard about — the loose affiliation of very young Los Angeles-based African-American rappers who make up the hip-hop crew Odd Future, centered on a performer who calls himself Tyler, the Creator. It’s also a piece of intense, in-depth investigative reporting on the evolution, identity, and whereabouts of a legendary figure in the O.F. domain known as Earl Sweatshirt, who turns out to be the son of South African poet Keorapetse Kgositsile, whose work inspired the group of Harlem-based proto-rappers The Last Poets.

Some smaller pleasures: Mark Singer’s Talk of the Town piece about playing the telephone game on the High Line with 200 people passing along a phrase from a Tibetan Buddhist sutra; Michael Schulman hanging out with Kathleen Marshall looking at kinescopes of old performances of Anything Goes to prepare for the Roundabout revival; Hilton Als’ review of By the Way, Meet Vera Stark, which made me reconsider how much fun it must be for the actresses to perform that show; and then of course, this Roz Chast cartoon: