This week’s Style Issue is one of those exceptional issues, stuffed with goodies, that reminds me why I revere this magazine. The writing is so excellent that the magazine frequently serves as a writing manual. This issue alone has five exemplary non-fiction reporting stories that are marvels of fine prose that I would hand out to students if I were teaching a writing class.

Take, for instance, the lead of David Owen’s “Survival of the Fitted”: “On my first day in Colombia, two women in an old Toyota drove me to an industrial park on the outskirts of Bogota. There, in a building that from the outside looked like a warehouse, the man I’d come to interview — early forties, black hair, not tall — shot me in the abdomen with a .38-calibre revolver.” The story is about bulletproof couture, and it’s vintage David Owen, who has made a name for himself by focusing on fascinating and unpredictable array of little-scrutinized pockets of contemporary culture. His writing style is both crisply journalistic and full of facts but also endearingly droll. For instance, he discusses cultural differences in armored clothing, which cultures have to deal with knife attacks more than gun attacks, and casually mentions that “Most ammunition used by soldiers…goes right through the kinds of bulletproof material that are worn by cops and recording artists.”

I’d never heard of Daphne Guinness and wouldn’t have thought I would be interested in reading about an eccentric aristocratic fashionista, but Rebecca Mead is such a good writer that I never lost interest in reading her engrossing story about this creature who clomps through the world in crazy designer shoes without heels, who was a close friend and customer of the late Alexander McQueen, and whose grandmother was Diana Mitford. Mitford, Mead reminds readers, married Sir Oswald Mosley, the founder of the British Union of Fascists, at the home of Joseph Goebbels. Among the wedding guests was Adolf Hitler, with whom Diana’s sister Unity was very close. Mead reports: “When [World War II] broke out, Diana spent three years in London’s Holloway prison. ‘She told me she read a lot of Racine,’ Guinness said. Meanwhile, when Britain declared war on Germany, Unity Mitford short herself in the head. ‘Why didn’t Unity shoot Hitler instead of herself?’ Guinness said. ‘Then we’d be descended from heroes instead of villains.’ ”

Whenever this annual issue rolls around, I always think to myself, “I don’t care about fashion,” and I don’t really. But again I could not resist reading every word of Susan Orlean’s profile of Jean Paul Gaultier (above). Among the exotic creatures we meet in this story are Donna and Meghan Spears, who own a designer boutique called Consortium, in Oklahoma City, and Gaultier is the best-selling designer in the store. “I admitted to the Spearses that I wouldn’t have guessed that Gaultier had many fans in Oklahoma, but Donna said, ‘Oklahoma City is much more progressive than people think. In our target market, everyone has more than one home, more than one airplane. In the past, everyone went to Dallas or Aspen or La Jolla to shop. Now they come to us. At the end of the season, we never have any Gaultier left.’ ” Plus — and I guess this is a generational thing — I never get tired of noticing how matter-of-factly fashion writers for the New Yorker and the New York Times (most of them women) write about the personal lives of famous designers (most of them gay men). There was a time when gay private lives were just never mentioned in the pages of these magazines. Just saying.

There are also two emotionally affecting gay life stories mentioned in passing in Peter Hessler’s terrific article “Dr. Don,” which focuses on a small-town pharmacist in a hippie-dippie utopian enclave in southwestern Colorado, a world I would never have imagined or known about before reading this story.

Anytime Janet Malcolm writes something for the New Yorker, you know that inevitably she will find some way of referencing some awkward complicated relationship between the journalist and her subject, and that does indeed show up halfway through her profile/essay about German photographer Thomas Struth, whose portrait of the Queen of England and the Duke of Edinburgh she dissects meticulously. I also learned from her the typically German compound expression Vergangenheitsbewältigung, which means “comes to terms with the past.”

Hilton Als has been thinking a lot about Stephen Sondheim recently. His Critic-at-Large piece about Diane Paulus’s new production of Porgy and Bess carefully and thoughtfully rebuts Sondheim’s now-famous letter disparaging the remarks Paulus and playwright Suzan-Lori Parks made about the Gershwin opera in a New York Times Arts & Leisure story several weeks ago. Perhaps not surprisingly, he sides with Paulus and Parks in their revisionist take on Porgy and Bess and ever-so-gently trashes Sondheim for championing DuBose Heyward. That doesn’t stop Als from also writing a beautifully considered review of the current Broadway revival of Follies.

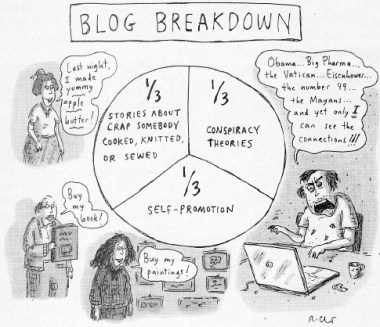

I also liked Jenny Diski’s piece on the history of shoplifting and Anthony Lane’s review of Drive. And, of course, there’s always Roz Chast: